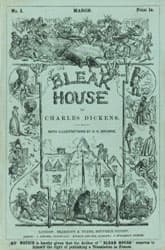

Bleak House

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies

First serial, 1852

First serial, 1852First publication

1852–1853 as twenty-part serial with illustrations by Phiz

Publication in book form

1853

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, crime, mystery

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 166,000 words

The best of novels, the worst of novels

Bleak House has its ardent admirers who declare it among Charles Dickens's masterpieces, as well as its detractors who call it one of his most grotesque potboilers.

The author's strengths are here in spades: memorable characters, a clever twisting plot and related subplots, heart-wrenching drama, pointed social commentary. Plus some of the most innovative passages seen in Dickens's work so far.

On the other hand, about those memorable characters.... Too many!

Dozens. Taken altogether in one novel, they're hard to keep straight. One is constantly flipping back through pages—whenever a Boythorn or a Bagnet or a Jellyby or a Jobling re-appears—trying to recall: was that the maid of the gentleman who's a friend of the lawyer for Jarndyce's nephew or...?

It's been complained the characters of Bleak House, like the denizens of any Dickens novel, are one dimensional. What makes most of them memorable, it is said, is that they are cartoons, individuated with one or two outlandish characteristics that Dickens highlights whenever they come on stage. Meanwhile, the leading characters—in this case, including the orphaned Esther Summerson, her guardian John Jarndyce, and her friend Ada Clare—are supposedly too bland, all uniformly and unrealistically good-hearted souls.

Beyond reportage

These charges are justified, but unimportant in my opinion. Even a stickler for realism, such as present company, may also recognize that in works of fiction—in artifice—something has to give in order to condense and emphasize, or else we would bee stuck with unexamined, unenlightening reportage.

With his colourful characters and sometimes simplistic narrators, Dickens is able to get to important truths about the world in which they and we live, whether the insights concern quandaries of the heart or tragedies of social injustice, each kind of which is central to Bleak House.

But it's just so long. Read a short, quick-moving and still colourful novel, like the author's Hard Times, and then move on to the painfully drawn-out Bleak House (which actually was published a year earlier) and you'll wonder how the same man could have authored both.

Bleak House is Dickens's most Shakespearean novel in that every character speaks what they are thinking. Speechifies rather. What they're thinking and why they're thinking it. And why they're saying what they're thinking.

Except, of course, when it serves the purpose of the plot for us not to know what they are thinking. Lady Dedlock (another wonderful Dickensian name) keeps her deep, dark secret from readers until the time is dramatically ripe, and from almost all the other characters until her death. Inspector Bucket misdirects us until he is ready to uncover the murderer. Even the narrating Esther who effuses over day-to-day trivia hides crucial plot points. It's difficult at times to understand exactly how her diary entries are to be taken, as sometimes they seem to be written as events are taking place (how is this supposed to be done?), while other times they seem to be written in retrospect with knowledge of what is to come.

A bad joke?

I have wondered at times whether Dickens purposely drags out the exposition and dialogue of Bleak House to reflect his theme of the slow pace of the soul-destroying British justice system at the time.

And not just the judicial process is satirized. The parliamentary establishment, the corrupt political process, the class system and the plight of the impoverished—especially children—come in for some of the most clever ridicule.

But it would be a bad joke to make readers experience the desperation of many of the characters by spinning out the prose to seemingly interminable lengths, wouldn't it?

I don't know if this is beyond Dickens. Though perhaps another intuition about his purpose here is more correct. Perhaps, writing in instalments for the periodicals of his day, the great author was every week casting about in one subplot or another, writing his heart out for this or that scene, producing as much as he could in the hopes that out of all the words something significant would emerge to take over the novel as a whole. I'm not sure he ever found this unifying direction in Bleak House, but his facility as a writer brought numerous insightful and entertaining moments up from the depths.

And many readers do seem to find Bleak House a grand entertainment, despite all that's been said about it here. Truth be told, any of the individual scenes are brilliant small plays, complete with minute stage directions. And if one takes time with the entire novel, living in it for an uninterrupted period, the pieces do manage to hang together.

Like many of the greatest British novels of the nineteenth century, Bleak House provides a sweeping view of all levels of a society with diverse interests and numerous subplots.

And yet Dickens manages to pull the threads together for a satisfying conclusion. Or rather, for several satisfying conclusions. If you get that far.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies