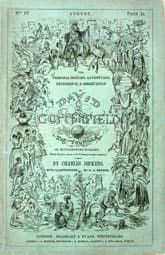

David Copperfield

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies

Serial, 1849

Serial, 1849Original title

The Personal History, Adventures, Experience, and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery

Also known as

The Personal History of David Copperfield

First publication

1849–1850 in instalments

First book publication

1850 in two volumes

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, buildungsroman, autobiographical novel

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 357,000 words

Half great, half good

The first half of David Copperfield, concerning the struggles of the young boy against repressive step-parents and draconian schoolmasters, is one of the greatest, most affecting novels ever written.

The second half, as the boy grows into a famous writer involved in the intrigues of his friends and lovers, is a merely good and affecting Dickens novel.

One would be less disappointed with the second half if the first were not such a masterpiece.

The novel starts very quickly with David's birth and the travails of his childhood. It follows—so honestly and naturally that the plot seems to write itself—through his various persecutions by elders to his adolescent introduction into the lower rungs of society amid the poor fishermen on the coast and the poverty-stricken Micawber family in the city. Dickens appears not be writing this at all but reporting it as it happens. The reader has no time to consider how well the story is told but is swept along on a tide of anxiety and hope.

Seeing the puppet master

But then, as the boy becomes a young man, starts making choices and moves up in the world, we begin to see Dickens pulling strings. We notice how everything works out so handily with all the good characters in the novel, how they all immediately love each other and come together so easily to oppose the evil characters.

We notice Dickens consciously tugging at the heart over the fate of David's objects of affection, Dora and Emily. (Why David is attracted to the bubble-headed Dora in the first place is a mystery to me, and the whole drawn-out, melodramatic subplot of the search for the eloped Emily causes me to skip entire pages in boredom.)

We notice how conveniently the good characters who have fallen on hard times are dispatched to Australia where they all thrive, while the more fortunate good characters all find prosperity, love and happiness in Britain.

We notice how an incredible set of coincidences brings together three of the novel's villains in a jail in a late chapter to give Dickens a chance to tie up diverse loose ends and make a statement about prison reform. Good hearts and tolerance overcome all social injustices, while the greedy and envious suffer their own dire rewards.

Now, this critical division of the novel into halves is perhaps too neat. To be fair, the shift occurs gradually—this Dickensian movement between demythologizing (mainly in the first half of David Copperfield) to enforcing new myths (mainly in the second half).

You can find this interplay throughout Dickens's works, although seldom so evenly sorted. It's what leads some people to acclaim Dickens a hard-eyed social critic at the same time as others decry his unrealistic plots and excessive sentimentality, as if they were talking about two different writers.

Accommodated characters

The most astounding aspect of David Copperfield though is that it is bursting with intriguing characters.

David's lovable nurse Peggotty who fills in for his weak widowed mother....

The stern brother and sister Murdstone who, as his step-parents, make the lad's life a misery....

Creakle, the ignorant, vicious schoolmaster....

David's eccentric aunt Betsey Trotwood who takes him in....

Her lodger Mr. Dick, an amiable lunatic whose thoughts are repeatedly commandeered by the decapitated King Charles....

Mr. Micawber, a well-meaning, verbose ne'er-do-well who has become a bigger legend than Copperfield....

Uriah Heep who pretends humility but whose name has become a watchword for a scheming villain....

Many more. No wonder it's been joked that David Copperfield, considered a stand-in for the author, is the least interesting character in the novel that bears his name.

The creation and handling of so many memorable characters in a single, more or less cohesive novel is such an accomplishment that it seems niggling to complain about the seams of the novel sometimes showing.

I may wish that the moving reportage of human suffering in his society had led Dickens and his characters to natural consequences in the novels, rather than to heart-warming panaceas.

But if it had, Dickens's work might not have accommodated all the characters we've come to love or hate. It might not have been as popular as it was and might not have endured to be read by us today.

It has also been said that Dickens himself must have felt that in this supposedly autobiographical novel he did not get his own character right. That he made David too bland and too good as he grew older. He was to take another crack at it a decade later with Great Expectations, a somewhat similar story but with the young lead turning out quite differently.

This speculation may or may not be justified but it doesn't change the fact that the earlier novel, with all its flaws, provides one of the greatest literary experiences you can ever laugh, cry and sigh over—sometimes all at the same time.

So take what you can. Celebrate the genius in Dickens's David Copperfield and wink at the rest.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Text • At the movies