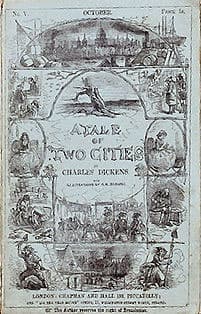

A Tale of Two Cities

Critique • Quotes

Serial, 1859

Serial, 1859First publication

1859 in 31 weekly instalments

First book publication

1859

Literature form

Novel

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 139,000 words

The human mystery

It's the most political of Charles Dickens's novels, it's the least political—even anti-political—of Dickens's novels in some ways. But its positions on politics, revolution, mob rule, democracy and reformism has tended to dominate the discussion of A Tale of Two Cities.

The first time I read the novel it was a disappointment. I knew Dickens as a crusading writer exposing the tragic human consequences of rampant capitalism in his time.

But in A Tale of Two Cities I saw him pulling back from concerted action against social injustice and adopting the British establishment's horror over the French Revolution, focusing on the uprising's excesses. Worse, he used an improbable melodramatic story of individual romance and personal sacrifice to turn readers attention from—and against—the larger issues being played out in England and France in that tumultuous time.

However, years later when I picked up the novel again I realized that first reading had been too quick, in my eagerness to catch the admittedly thrilling narrative highlights. I resolved to re-read it more carefully and slowly, much as in Dickens's lifetime it had been read by an eager public who'd had to wait for weekly instalments. The results were revelatory.

Mysteriously narrated

Despite A Tale of Two Cities being one of Dickens's most heavily plotted full-length novels, with a basic story-line among his best known, much of it is written in a curiously indirect style. (Lending itself to another one of those ambivalent parody critiques: "It's Dickens's simplest novel, it's Dickens's most complex novel.")

He often eschews in A Tale the long descriptions he's known for and jumps right into plot developments without giving the reader vital information up front, such as who the characters involved are or what they are trying to do, leaving it all to become clear through the chapter's progress—or later in the novel. The whole first "Recalled to Life" section is narrated thus mysteriously: what's the meaning of this enigmatic message received by a coach passenger? Why does it whip him into action and what's his mission? Who is being revived? The latter question is not completely answered until late in the novel. Even one of the first answers to this question raises another mystery which is oddly avoided by all until its revelation catches them off guard near the end: why was Dr. Manette imprisoned in the Bastille in the first place?

Dickens is adept at posing such mysteries and then misdirecting our attention, so that we brush them off until they come back to bite us as sharply as the characters themselves. For example, Dr. Manette asks Charles Darnay to hide his family name from his fiancée, Manette's daughter. Why? He won't say, so it's probably just part of his obsessive craziness and there's so much else going on that we don't ponder it. Until it becomes of great, and potentially fatal, consequence.

Passages about events in London and Paris, the two cities of the title, feature shadowy figures who gradually take shape in the reader's mind before eventually playing publicly decisive roles.

Dickens starts an early chapter with a reflection on the difficulty of really knowing anyone. Included in that paragraph is: "No more can I turn the leaves of this dear book that I loved, and vainly hope to read it all.... It was appointed that the book should shut with a spring, for ever and for ever, when I had read but a page." The book he's referring to is metaphorical, of course, representing fellow beings—friends, family, lovers. But A Tale of Two Cities also appears to be an attempt to hold that book open a little longer. It recognizes the unsolvable mystery of humanity, it works within that mystery and draws out as much as it can before finally snapping shut with the expected ring of a guillotine.

One of the discoveries then is that every heart has its secret reasons. Everyone has something to hide, whether they know it or not. If we dig deep enough, we may find part of what drives anyone. Much of each person's behaviour to others is set by others' behaviour toward them or their class. Even the most seemingly evil characters, such as the bloodthirsty Madame Defarge, have their private hells that have propelled them to their seemingly evil deeds.

Warning to the new ruling class

Returning to the political theme, we can see in all his narrative detail that Dickens finds ample reason for the oppressed people of France—and of England for that matter—to rise up violently. The excesses of the French Revolution were terrible all right (though not as terrible as its aristocratic critics claimed, as Dickens is careful to avoid repeating the most hysterical charges) but they were brought on by the nobility's centuries-long reign of terror in both countries.

He obviously does not condone the violence but he understands it. The sense of his most authorial comments seems to be dismay that the upper classes had not moderated their behaviour to allow a more gradual improvement to the lot of the masses of people. The historical novel addresses the seventeenth-century remnants of the medieval aristocracy, but Dickens is really warning the Victorian-era bourgeoisie, who took over the ruling class positions thanks largely to the ousting of the aristocracy in upheavals such as depicted in the novel.

In this, Dickens is the eternal liberal reformer. Correct the worst abuses. Watch what seeds you plant in the hearts of the lower classes, else your heads may roll on the next chopping blocks.

But Dickens is also the eternal optimist. In A Tale's personal story of love and redemption, which so annoyed me originally, he is actually showing the other side: with caring, the human heart may also develop its reasons for good. Darnay repudiates his upper class allegiance to find love and family elsewhere—and to win release from prison at one point. Dr. Manette is returned to life by the efforts of his friends and daughter. The formerly self-interested lawyer Sidney Carton is led by his own commitment to a woman to make the ultimate sacrifice. A surprising number of other smaller instances of altruistic behaviour abound alongside the many large and small, vicious and vindictive actions in this tightly constructed novel.

So in the end is it really a tragedy? It's certainly not a comedy. But a close reading brings out the ultimately positive theme. In this, it's like Romeo and Juliet, which is also officially considered a tragedy but which much of its audience considers a great romantic story of love conquering divisive social conventions.

In A Tale of Two Cities, love (or kindness or goodness) doesn't exactly conquer anything. It's just part of the reality that also includes hate (or meanness or evil)—the reality that we ourselves create with our individual and group behaviour.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes