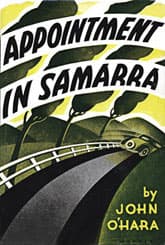

Appointment in Samarra

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1934

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 98,000 words

Fate in America

Appointment in Samarra is about as perfectly structured and written a novel of American social critique as you could find in the first half of the twentieth century—up there with Babbitt and The Great Gatsby.

True, John O'Hara doesn't display Sinclair Lewis's gift for hyperbole or Scott Fitzgerald's lyrical brilliance, but his novel is also a more down-to-earth account of the United States' class system. It is less a fable than Gatsby and more a factual reporting of the people in the various strata it addresses.

While both Fitzgerald and O'Hara may have thought the rich are different from the rest of us, O'Hara saw our fates intermingled.

The overall story arc follows the slide of one Julian English from the peak of Gibbsville (read Pottsville, Pennsylvania) society. The story begins actually from the perspective of one of his employees, who wakes up on a winter's night to the racket of the country-club set having a Christmas party and rolls over to make love to his wife in their cozy bed. Their attitude to the noisily affluent is a mixture of envy and gratitude that they don't have the personal problems of the Englishes and their ilk.

For Julian and Caroline English are having another of their "battle royales", this time over his jealousy of a man he suspects of flirting with his wife. Not that he would make a scene about it of course. He's too much a gentleman and Reilly, the other man, is too important in Gibbsville circles.

These first short sections of Appointment in Samarra are models of seemingly relaxed writing that nonetheless quickly tighten the dramatic screws, until...until....

Until exactly what you don't expect to happen happens, though in retrospect it seems inevitable.

It's only a small social faux pas but word spreads quickly through Gibbsville and Julian English's world starts falling apart. Over three days, the owner of the city's premier car dealership, who depends upon the patronage of his wealthy contacts, seems to take every step to exacerbate his worsening social position. In the course of his decline he interacts with rich in-laws, middle-class friends, religious figures and even local gangsters, and the usually drunken English manages to turn every encounter to his own detriment.

So while The Great Gatsby concerns a failed pretender to the ruling class, Appointment in Samarra features a bona fide member of that class dropping out of it. What really sets it apart thematically from Gatsby though is that the top tier in Appointment are not the aristocratic, idle rich who have little to do, besides vacation and have affairs in the pleasure spots of the world, but are what we might (with tongue partly in cheek) call the working rich: the business elite who run any sizable North American community.

O'Hara performs a small miracle by uncovering this interconnectedness of people and classes in such a community mainly by suggestion, in the course of a simple plot that unfolds almost in real time. The ancient unities of place and time are achieved, while hinting at several further dimensions.

The old tale

This is not to imply Appointment in Samarra is a philosophical or sociological treatise. Far from it. It's a quick story with pages of some of the most realistic dialogue you'll ever read, plenty of side trips down memory lane and scenes of female sexuality that were scandalous for the book's time. They all swirl around a man spiralling down toward what seems his inevitable fate.

Hence the title, taken from W. Somerset Maugham's retelling of an old Babylonian tale, presented as an epigraph to this novel.

The greatest irony though is that near the end of the novel we realize Julian English's position is not as hopeless as he thinks. But by then it's too late and he delivers the final coup de grâce.

Which makes one wonder. Are we to think his fate is set from the beginning, as in the old tale, or are we to think his own self-destructive dread of disaster dooms him, preventing him saving himself with means that are actually within his reach?

Nature or nurture? At the beginning of this article I was going to refer to O'Hara's novel as a model of American naturalism, since his style is casual and anti-romantic and the plot unfolds nearly scientifically. But then the question is raised whether it is Julian English's background and surroundings that shaped him or some psychological quirk within himself. And is there a difference?

Others have written about Appointment in Samarra as if it is another Depression-era cautionary tale, in which the high-flying nouveau riche of the Roaring Twenties (Fitzgerald's era) come crashing down in the Dirty Thirties. There may be something in this, in that the zeitgeist likely inspired O'Hara storyline—he himself as a young man had had his own high hopes dashed by the economic downturn—but I doubt he intended any such moral to be drawn from the novel.

Rather, most craftily and succinctly in Appointment in Samarra, O'Hara is recording what he sees in the society he knows without separating cause from effect—or the individual from the social.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes