Empire of the Sun

Critique • Quotes

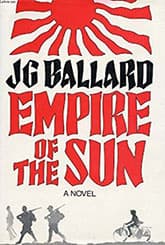

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1985

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, historical

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 115,000 words

A boy's adventures in the furnace

After his post-apocalyptic tales of psychological horror, after his scandalous work on human mangling and perverse sexuality, J.G. Ballard turned to producing his most conventional, biographical and realistic novel in 1984.

And it proved to be his most deeply disturbing work yet.

Empire of the Sun is not disturbing in the way of superficially shocking plot twists that startle you briefly until you move on to the buildup for the next thrill.

The story of a British boy's experiences during the Japanese takeover of Shanghai during the Second World War may be rife with cruelty, disease and killing—more than in any other novel I can think of. But there are no operatic explosions of melodrama. There are no overwhelmingly horrid scenes to make you cringe and want to put the book down to recover for a minute.

The writing, presenting the hellish war from the boy's perspective, is too controlled for that. The boy Jim accepts each blow as it comes: separation from his parents, capture by enemy soldiers, alliances with protectors who betray him, semi-starvation and disease in prison camps, sudden vicious attacks, bombings, death and dying all around him. He takes each turn for the worse with a quiet resignation, as if it's part of an occult adventure in which he has a meaningful role. He even finds small measures of enjoyment in his miserable daily life.

Ballard never gives in to the temptation to wallow in pity, sorrow, or any of the other emotions for which we expect such scenes to be exploited. He never lets horror overwhelm Jim—or us.

Absorbing the terror

This is wise writing. If we were exposed to periodic hysterics, the tension would be released. We would have the pleasure of venting over life's unfairness.

Rather we watch the boy incorporate every new terrible discovery into his youthful, incomplete world view, and we sense—rather than are told—how the drip-drip-drip of misery is affecting him. With him we hang on to a shred of optimism, even if we more worldly adults know it's misguided. We follow with foreboding his desperate schemes to befriend enemies and help less fortunate fellow prisoners. We laugh sympathetically at his attempts to continue educating himself long after schools have disappeared from his world.

And then when Jim witnesses from a stadium prison camp one of the most catastrophic acts of warfare in history—the dropping of an atom bomb on Japan—the moment comes and goes in typically journalistic text. Though it gives the novel's title a new resonance:

But a flash of light filled the stadium, flaring over the stands in the southwest corner of the football field, as if an immense American bomb had exploded somewhere to the northeast of Shanghai. The sentry hesitated, looking over his shoulder as the light behind him grew more intense. It faded within a few seconds, but its pale sheen covered everything within the stadium: the looted furniture in the stands, the cars behind the goalposts, the prisoners on the grass. They were sitting on the floor of a furnace heated by a second sun.

Even this fateful event is merged into the boy's personal mythology:

Jim smiled at the Japanese, wishing that he could tell him that the light was a premonition of his death, the sight of his small soul joining the larger soul of the dying world.

Through such reporting, Jim reveals an ambivalence toward all manner of issues we might consider obviously one-sided. He admires the Japanese invaders at times and develops attachments to some of his captors. He seems to have mixed feelings about the war itself. He becomes enamoured with the notion of his own death, as in the above-cited passage.

And this is part of what's disturbing. On one hand the beyond-chilling events experienced and witnessed by the youngster under unimaginably horrible circumstances and on the other hand the calm, practical attempts to override them.

Strange world

Empire of the Sun is often considered an anomaly among Ballard's work, a kind of sidestep from his dystopian science fiction like The Drowned World (1962) and The Crystal World (1966).

But much of what has been said here about Empire can also be said about those earlier novels. In them, the natural world is typically undergoing a change, radically alien to humanity, and yet the central human characters find something within themselves responding to the threatening new reality. This summary applies to Empire as well, except now it's the civilized world that has been made strange.

The big difference between Empire of the Sun and Ballard's earlier works though is the realistic setting. The time is not the science fiction future but the twentieth-century past. The events depicted in the novel actually happened. The horrors were real.

That makes the boy's experiences and his inner responses all the more chilling. And, in a weird way, kind of uplifting.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes