Murder on the Orient Express

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

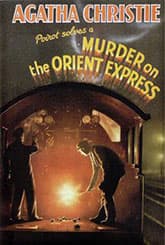

First edition

First editionAlso known as

Murder in the Calais Coach

First publication

1934

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Crime, mystery

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 66,000 words

Re-riding the mystery train

A lot of mystery novels don't stand up to repeated readings. Makes sense. Once you know the ending—once the mystery has been solved—the tension in the slow buildup to the conclusion is dissipated. Plot holes and thin characterizations, overlooked in the first rush to resolution, become glaringly obvious the second time through. After a first reading, best to close the book with a satisfied sigh, revel in the cleverness of its finale for a few minutes, then put it away, never to be re-opened or thought about again.

Against all odds, some great writers in the genre are able to invest their works with enough insight, subtlety, engaging style and other sustaining literary qualities that they can be read repeatedly over the years—each time offering the reader a different, possibly deeper experience.

Unfortunately, Agatha Christie is not such a writer. At least not in Murder on the Orient Express. The novel featuring her popular sleuth Hercule Poirot is practically the stereotype of a mystery whose acclaim is based almost entirely on its unusual solution of a puzzling mystery, and on a willingness to overlook all the less-than-believable characters and even more unbelievable circumstances that lead to the ending.

Stunning end

Actually, the finale of Murder on the Orient Express presents two major surprises: the solution to the mystery and what Poirot does with it.

The former is handled in the common cozy fashion with the detective bringing all suspects together in one room to review the case and cast accusations about, but presenting two different solutions to the crime—both an obviously flawed conjecture and a painful reconstruction that answers all questions—leaving it up to others to decide which to accept. Then Poirot dismisses himself from the scene and the novel closes suddenly with no editorial comment on the morality of it.

It must have been a stunning conclusion in its time. Ahead of its time really. Though the continuing cinematic treatments of Murder on the Orient Express seem to feel the need to add a little moral questioning on the part of Poirot or his colleagues.

And the adaptations have indeed continued, with at least eight versions made for movies, TV, stage and video games since 1974, as the novel has remained one of the three favourite Christie mysteries—as well as one of the most popular crime and mystery works ever.

Which is hard to understand when you set aside the startling conclusion. The narrative format is like several Christie whodunits, with Poirot brought into a secluded gathering of diverse individuals—in this case in a train carriage—to investigate an unusual murder. He proceeds to interview each of the suspects and witnesses, uncovering their secret connections with each other and with the victim.

This all rather laborious. I suppose the reader is expected to try to track the myriad movements and motives of all those interrogated, but they're hard to keep straight.

Besides, any British mystery reader knows that these revelations are unlikely to bear on the ultimate discovery of the murderer. The key usually turns out to be some seemingly inconsequential bit of evidence that the detective has noticed or some little bit of pop psychology he comes up with. For all his talk of using the "little grey cells" to solve crimes, Poirot depends an awful lot on his assessment of character and on an ability to emulate a lie detector.

Good guessing

At one point in Murder on the Orient Express, the little Belgian detective says:

If you confront anyone who has lied with the truth, he will usually admit it—often out of sheer surprise. It is only necessary to guess right to produce your effect.

Here he almost gives away the mundane secret of his success. Like Sherlock Holmes and other fictional detectives who claim a deductive method, when it comes to the crunch Poirot often relies on guesses. Dressed up as insight into the human heart.

And, speaking of quick assessments of character, Murder on the Orient Express gives Christie free rein to indulge her penchant for stereotypes. The brashy, slangy American. The haughty Russian aristocrat. The effusive, possibly criminal, Italians.

The evidence uncovered is less than circumstantial. The inference drawn, as startling as it is, is no more convincing. No wonder a critic like Raymond Chandler was outraged at the unreality of it all. (See the Agatha Christie commentary for more of Chandler's take on this novel.)

I don't recall whether I noticed all these failings the first time I read Murder on the Orient Express some years ago. At the time I may have been one with the admiring world that was surprised at the clever and abrupt ending.

My mistake was reading it a second time.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies