Henry IV, Part 1

Critique • Quotes

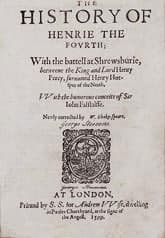

Title page in first quarto, 1599

Title page in first quarto, 1599First performance

1597

Literary form

Play

Genre

Historical, comedy

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Five acts, 3,081 lines, approx. 24,000 words

The prince and his papas

I once read all Shakespeare's historical plays in chronological order. Not in the order he wrote them, but in the order of the historical events they supposedly relate.

Like many before me, I discovered that (1) the historical plays are of quite uneven quality, (2) the historical plays are not historically accurate, (3) you don't have to know history to appreciate the best of them, and (4) my school teachers were right: if you read only one, then Henry IV, Part 1 should be it.

Part 2 is almost as good and Henry V is all right too. But it's Henry IV, Part 1 that introduces the ever-popular rascal, Falstaff, whose subplots steal the play from the more serious and boring themes of maturation and responsibility exemplified by the young prince Hal and his father Henry IV.

This is also the play in which Hal first makes the transition from fun-loving member of Falstaff's band of rogues to respectable prince-in-waiting and comes to his father's defence. This makes for greater drama than in Part 2, which more or less continues the transformation and is most interesting for Hal's completed discarding of the hopeful Falstaff in the end.

Reading all the historical plays in order also made clearer for me the biases Shakespeare wove into the dramas, based either on his self-interest as a playwright dependent on the pleasure of his current monarch (Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudor line) or on the unreliable sources of the day from which he drew his plots. The Henrys IV, V, VII and VIII were definitely good guys in his books.

For England

Shakespeare was writing when the British monarchy had long given up the Divine Right of Kings (although it was to make a bit of a comeback with the later Stuart kings) and ruled as the accepted embodiment of the nation. A king or queen was seen as sacrificing his or her own personal benefit for the sake of England. Symbolized by the monarch, Britain was reaching new heights of commerce, exploration and art.

Backing royalty against the rebellious parties that would break up the kingdom was to promote not an individual despot, but to promulgate the unity of the nation in this period of growth. In Shakespeare's plays, characters are always warning that a united England can never be defeated from without, only by internal division. As a dramatic device, the internal divisions are often mirrored by contradictions within the hearts and minds of the monarchs at the centre of the action. Their resolution of these contradictions, or their overthrow, is what leads the nation forward.

This was a period when the interests of the people seemed to coincide with the interests of a dutiful monarch. In the history plays, we see Shakespeare's favoured monarchs are those thought to have had the interests of the nation most at heart: the Henrys (though he has to spin-doctor the behaviour of Elizabeth's father, Henry VIII, quite a bit to make him fit, while Henry VI is represented as pathetic more than bad and not as evil as the Yorkists who seek his overthrow). The kings he disparages are those portrayed as placing their own interests above the nation: John and the latter Richards, II and III.

In Henry IV, the king is certainly cast in the mould of duty before self—"uneasy lies the head that wears a crown" (from Part 2) and all that. The prince's transformation is seen as a response to this duty, rather than to personal ambition, and in Henry V the prince, now king himself, becomes the greatest embodiment of the English nation to date in his patriotically inspiring performance at the battle of Agincourt.

Shakespeare though is hardly a jingoistic sword-rattler. He also knows many in his audience side with Falstaff's own cynical views that "honour is a mere scutcheon", and the exploits of this bumbling rogue are played to their entertaining hilt, to make Hal's acceptance of princely responsibility all the more profound.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes