All Quiet on the Western Front

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

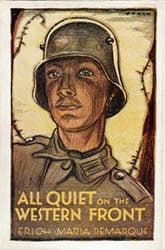

First American edition, 1929

First American edition, 1929First publication

1929

Literature form

Novel

Original title

Im Westen nichts Neues

Genre

Literary, war novel

Writing language

German

Author's country

Germany

Length

Approx. 67,000 words

Translations into English1929 by A. W. Wheen, 1993 by Brian Murdoch

Simply told nightmare of war

All Quiet on the Western Front is the kind of book you've heard about forever as a Great Book, one you've always meant to read some day, and yet it sounds so heavy and depressing and so...so worthwhile...that somehow you put off getting to it.

And then you finally do read it and, whew. You want everyone else to read it. Now.

The topic is heavy, the message may be depressing, and it is so worthwhile. But it is also a wonderful read. A seemingly easy read that sucks you in and wrings you out.

It purports to be the testament of one Paul Baumer. He is a German soldier during World War I. And his story is written entirely in simple, short sentences.

Baumer starts telling his story in 1917 after half of his company has been wiped out, but in flashbacks he introduces his comrades in arms as he met them in school or during the early days of the war. He details how they lived, fought and died together. Reading this I had my first real understanding of the famous camaraderie in the trenches, of how soldiers become closer than lovers, of how this relationship becomes their spiritual driving force, far from any noble ideas of fighting for a cause like God or country.

In these extreme circumstances Baumer tries—and usually succeeds in trying—to convey inner states on the very edge of describability.

It's an unrelenting nightmare. The battle scenes and the life among the muck and the bombs and the splinters that can suddenly pierce the brain of the man beside you so he dies while you continue conversing with him—they're all hellish enough. But to say it's unrelenting is to mean it goes beyond the battlefield as some of the most painful chapters are those that take place in lulls between battles or when the men are away from the front. The psychological scars are permanent. While visiting his mother Baumer pounds his bed in mental agony, crying:

I ought never to have come here. Out there I was indifferent and often hopeless—I will never be able to be so again. I was a soldier, and now I am nothing but an agony for myself, for my mother, for everything that is so comfortless and without end.

Nor, we gather, does the end of war bring surcease for the survivors. Remarque's dedication to the novel speaks of "the men, who even if they may have escaped shells, were destroyed by the war".

And yet we never shed a tear for the characters in this novel. For Remarque's matter-of-fact language slips the horror past our inner censors, so we end up accepting the most awful things as everyday occurrences, just as the numbed soldiers do.

Then the story comes to a sudden, shocking halt in mid-1918 on the quietest day of the war, while the world awaits the armistice. And we grope back to our normal lives and we look back over the reading experience with wonder over what became of us for the duration.

The insanity of war

All Quiet on the Western Front was not the only great first-person account of the horrors of World War I in that era. Henri Barbusse's Under Fire (1916) had earlier covered soldiers on the French side to similar effect, though in a more heated, poetical manner. Robert Graves' autobiography Good-bye to All That (1929) provided the similar British experience. Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen gave voice to the soldiers' experience in memorable poetry. Writers of later generations, like Canadian Timothy Findlay in The Wars (1977) and American Pat Barker in her Regeneration trilogy (1991–1995), have returned to the same horrifying events of 1914 to 1918.

But it was Remarque's great novel that made the First World War representative of all futile, senseless, inhuman conflicts ever since. It is hard to imagine World War II novels, like The Naked and the Dead (1948) by Norman Mailer and Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, or the Vietnam War film Apocalypse Now, without All Quiet on the Western Front having first won our understanding of the insanity of war.

I'm not saying all wars are wholly insane or even wholly bad. But how they can unhinge the minds of the individuals caught in them was never more clearly revealed than in this novel, until maybe Pat Barker's Regeneration trilogy. And the very odd thing is that we do not come away from it depressed, but rather—inexplicably—uplifted. Perhaps "uplifted" is too fancy a word for it. Try "transformed".

I don't quite understand this effect but I get it, if you know what I mean.

So read this book. Now.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies