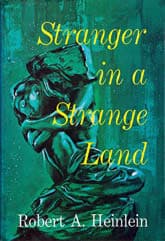

Stranger in a Strange Land

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1961; restored version 1990

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Science fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 160,000 words; restored 1990 version: approx. 220,000 words

What once was strange

Stranger in a Strange Land may be an old favourite of many readers who were first exposed to it in their youth, but the time may have come to drop it from the list of great novels.

It has certainly lost the cult status it had as an official book of the counterculture, alongside the The Little Prince and the works of Herman Hesse. Its ideas now seem dated and simplistic.

And it is certainly not as wildly popular now as when it moved from the counterculture into the mainstream in the late 1960s—though that peak of popularity may be impossible for any novel to maintain.

But what is most making me doubt the long-term value of Robert A. Heinlein's most acclaimed work is that I recently read the longer version, the 1990 edition that restored most of the cuts he had made to get it published in 1961. This presumably is the novel as the author envisioned it. It has accordingly been praised as superior to the originally published version. But it points up every weakness in the work.

Christ figure

It's very long-winded for starters. This might not be a bad quality in itself, but here it certainly is. I can't recall another novel that is so composed of speeches. Not dialogue. Speeches. Speeches that could have been cut in half and would have lost little.

The worst offending character is Jubal Harshaw, a lawyer hired to protect a mystically powered but wide-eyed Martian, a Christ-figure come to earth. Harshaw is an obvious stand-in for the author and is constantly spouting aphorisms and pronouncing on the natures of society, people, religion, sex, politics, you name it. Some of this is pointedly clever in a cranky Mark Twain kind of way. But it gets tiring after a while.

And then there's the alien, Valentine Michael Smith, providing a New Age philosophy (everyone is God, live in the present, love is free) for the narrow-minded, uptight, over-regimented earthlings. One wonders now how one could ever have thought this stuff was profound.

There are some striking narrative moments in the novel and some good irreverent cosmic twists that would do Douglas Adams (The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy) proud. But they're buried in the verbal poses, in the rambling doctrine Heinlein wants to disseminate.

Yet a certain affection for Stranger in a Strange Land remains. In part, admittedly, because it affected many of us at a particular time.

But also because it's heartening to see a modern writer addressing the big issues of our lives (society, people, religion, sex, politics...) so directly. Heinlein is a bold writer, unafraid to go where other writers, even in the imaginative field of speculative fiction, fear to tread. And he proceeds without a lot of literary subtlety.

Proto-fascist?

Alas, his didactic passages, which make up much of Stranger in a Strange Land, appear as clumsy pontificating now. And today much of it seems less than progressive, even odious. For example, Heinlein's sexual liberation seems to involve women serving as playthings for their free-thinking masculine masters in a kind of Playboy magazine fashion. He flirts with approving incest and pedophilia at times.

The book has also been attacked in retrospect as being proto-fascist, although this is less clear than in some other Heinlein works, like Starship Troopers (1959).

Although he was considered conservative politically—a libertarian no less—I doubt Heinlein would have felt at home in any official conservative movement. And other right wingers would be equally uneasy having him in their midst. For he's a thorough iconoclast without social filters. Whatever insights he has, whatever interesting ideas strike him, are bound to come pouring out in his writing and proclamations, regardless of the comfort of those around him. As shown nowhere more so than in Stranger in a Strange Land.

No single party or sect in America could take all of this novel to heart. In fact, Heinlein himself does not seem to do so. He thinks he's just tossing out novel ideas to stir up old thinking. This novel is a challenge thrown down to all, not necessarily well aimed or convincingly. For this it is still possible to appreciate the novel—either the original or edited version.

But this does not make it a great book for all time. Stranger in a Strange Land sdeems doomed to continue declining in the world's assessment, becoming an historical curiosity as its ideas recede in relevance.

But if our society takes a turn backwards to become narrow-minded, uptight and over-regimented once again, as it threatens to (some would say it already has), Stranger in a Strange Land could regain a certain cachet among the newly rebellious. It could return to shake us up again.

We need this kind of book when we need it and when we don't we don't.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes