Iliad

Critique • Quotes • Text • Translations

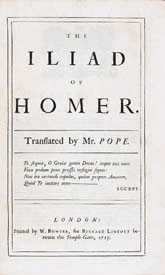

Pope translation, first edition title page, 1715

Pope translation, first edition title page, 1715Also known as

Song of Ilium

First publication

c. 800 BCE

Literature form

Poetry

Genres

Epic

Writing language

Ancient Greek

Author's country

Greece

Length

24 chapters, approx. 16,000 lines

Great stuff if you're an ancient Greek

Many notable literary figures have acclaimed the Iliad as a transporting work of art. I don't entirely get it. Even after having read several different translations of the epic poem.

I suspect any non-academic today who takes on the Iliad—that is, reads the entire work rather than just the most famous bits that have been dramatized in movies—might find it similarly disappointing.

In the first place, all the really juicy stuff about the Trojan War story, like how it started with love-smitten Paris whisking Greek queen Helen away to Troy and how it ended with that wooden horse trick—none of that is actually in the main narrative of Homer's massive poem. Rather it's recounted as memories of the past or predictions of the future.

The poet plunks us into the tenth and last year of the conflict between the Achaeans (as the Mycenaean-era Greeks are referred to by Homer, who also uses the terms Danaans and Argives) and the Trojans, who were probably Hittites and are portrayed by Homer as very similar to the Greeks, sharing the same gods, though slightly more exotic and eastern in their culture (King Priam having multiple wives, for example).

Much of the narrative is militaristic bombast. Along the way we can enjoy such exciting details as the listing of every Achaean leader, ship and horse that originally set out for the siege of Troy. And then every Trojan and Trojan ally who comes to the city's defence. And then long accounts of their slaying of each other, often with explicit gory detail of their fatal wounds.

And when they aren't slaughtering each other, they're making rousing speeches in their own camps to get the blood up for the next round of shedding it. A lot about of honour and duty in the service of slaying your king's enemies on whatever pretense anyone can come up with. All this may have been exciting stuff for the people of the time.

Death by design

To be fair, there is some juicy non-war material in the Iliad too. The "rage" of Achaean champion Achilles in the epic's first line is anger not against the Trojans he is supposed to be fighting but against one of his own colleagues, the purported leader of the Achaeans, namely Agamemnon. Their spat also started with disputed possession of a woman, Agamemnon having seized from Achilles a favoured captive to replace another whom Agamemnon had been forced to ransom back to the Trojans. For most of the poem a petulant Achilles sits out the battle, ignoring his comrades' entreaties, letting the Achaeans get beaten back by the Hector-led Trojans.

The gods, whom Homer has residing on Mount Ida in Asia Minor as opposed to the better known Mount Olympus in Greece, conspire daily in the affairs of humans, both in the big battles and in the petty disputes among the combatants and city dwellers. These all-too-human super-beings also spend much of their time squabbling among themselves, trying to win benefits for the Greeks or Trojans they favour. Homer practically invents in the Iliad the personalities of the ancient gods from the all-powerful Zeus on down, with which we have become so familiar. Zeus himself seems rather impartial, agreeing to help both sides of the war in turn. On balance, he seems to prefer a Trojan victory, but is undercut by his scheming wife Hera and some of his divine children who back the Achaeans.

It'd be wrong to see this, however, as capricious gods determining human fate. Rather, the destiny of each person or civilization appears in the Iliad to be set beforehand and the most the gods can do about it is to tweak the results. Their major involvement is ensure human fate is carried out as predetermined.

Achilles' great friend Patroclus fights in his stead, killing more than anyone else in the Iliad but is eventually brought down by Hector. This finally brings Achilles onto the battlefield to settle the fate of many Trojans, including Hector—and by extension the city of Troy. But Achilles, who was born of a goddess and a mortal king, knows and accepts that his own unavoidable end is approaching.

There hangs over the entire epic poem a sense of inevitability. There's a feeling in every scene that despite the momentary passions of the humans or divinities, we readers are viewing them from a higher perspective, we are seeing events unfold as they must, without regard for any sympathies we may have formed. At times, when we are engaged with those on the ground, this may appear completely unfair. Horrible even. But the underlying message is not that life is unjust. Rather it operates according to a larger justice than either we or our gods can fathom. I think it is this deep-seated expectation and dread in the human condition that gives some readers an exalted impression of majesty and authority in the Iliad.

What a Greek's gotta do

In defence of the Iliad's seeming militarism and bloodthirstiness, it's been argued the theme of the Iliad is really that war, particularly among the Aegean people, is terrible and pointless. The forensic-level descriptions of characters being slain are meant to show the real consequences of warfare. In which case the Iliad might fall into the same category as such horrific anti-war novels of modern times as All Quiet on the Western Front and Catch-22.

But I can't help but feel this is strictly a latter-day misinterpretation. Homer involves his readers (or listeners rather) in the struggles of the characters in the epic poem not to denounce war but to tell what was to them a fascinating story. He was inspiring great fellow feeling among the scattered communities of the Greek world, uniting them with feelings of a common heritage, including blood having been shed for national and personal honour.

Plus there are just too many characters and gods vying to be the protagonists of the Iliad, unlike in the Odyssey where we get to invest our sympathy in one great literary character. If we have to settle on one character in the Iliad though, it's got to be Achilles. We could read the Iliad as a tragedy centred on this flawed hero whose pride gets the better of him in dealing with his fellow Greeks and whose thirst for revenge gets the better of him in dealing with the enemy—such as, in his relentless pursuit of Hector although it's pretty certain Hector's death will lead to his own.

But this is imposing our modern notions of tragedy—since Shakespeare anyway—on ancient literature. I don't think Homer (or the likely numerous authors of the Iliad) meant to present an analysis of any individual character in directing his life outcomes. Rather we are shown how individuals fulfill their functions within the larger picture and meet their fates more or less honourably. War is neither good nor bad. How we conduct ourselves in it is what's important.

So we have Achilles, after getting over his petty personal grievances with his fellow Achaeans, being presented as a hero in slaughtering many men in battle, then cutting the throats of defenceless captives at Patroclus's funeral and holding games in honour of his dead friend. And then commiserating with the distraught father of a Trojan warrior he has killed. During the latter, he never repents. He never regrets his killing spree. There is no personal transformation. There is only Achilles, being Achilles. Being what Achilles must be.

Some may dispute this characterization, noting near the story's end Achilles gives in to the pathetic pleas of the Trojan enemy monarch to have the body of his son, Hector, returned for proper burial. Achilles and Priam share their personal miseries resulting from the war. See, war is tragic.

But this human connection comes too late and is too short-lived. Achilles seems to regret his yielding. And the war apparently proceeds.

Reading tip

To really follow the Iliad, it helps to know the mythical history leading up to where this poem begins—you have to recognize the great names thrown around and you have to try to imagine what it must have felt like to the Greeks at the time. There's no shame in reading prose summaries of the story online or elsewhere first, or getting a gloss of Greek mythology in general.

The Iliad is still worth reading though, even without that background knowledge, since so many of our cultural references are still based on the Homeric tales.

But you'll get much more out of it if either (a) you are an ancient Greek or (b) you get a good Iliad translation with notes to explain everything.

But, the supposed sequel, The Odyssey—now there's a tale we can all get into.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Text • Translations