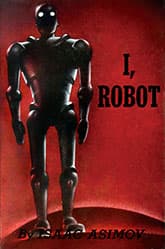

I, Robot

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1950

Literature form

Story collection

Genres

Science fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Nine stories, approx. 69,000 words

I, big robot fan

How strange that the most affecting characters Asimov ever created were robots. Perhaps it's the same phenomenon we find in film and television dramas in which synthetic creatures like Frankenstein's monster and the android Data become the most intriguing characters—as if their non-humanness tells us more about our humanity than flesh-and-blood characters can.

Speaking of Frankenstein, it was precisely to oppose that stereotype of the monster who turns against his creator that Asimov put to paper his most enduring words, the three Laws of Robotics that rule his human-friendly robots in his stories. For the record, the three basic laws are:

1. A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

They sound straightforward enough. But Asimov manages to wring problem after problem out of the application of these rules in his early robot stories. Many of the stories take the form of mysteries. A robot goes mad, a robot kills a human, robots go on strike, robots get religion—and a robot expert is brought in to figure out how this could happen, given the three laws.

The laws were first spelled out in Asimov's fourth robot story, "Runaround" (the robot-going-mad tale). But they were implied in all his robot stories, starting with the first one, "Robbie", about a robot and little girl who become attached to each other. Robots had been featured in fiction before but I think it must have been the optimism about android technology that so excited Asimov's readers in the mid-twentieth century. Interesting to read the stories now and realize Asimov was writing about the "future" as being the 1990s and early 2000s when this technology was expected to be commonplace.

Developing humanity

These stories are not well written in any fine literary sense and the ideas presented in the early tales are not particularly profound, at least not from our current perspective. The characters, like most Asimov characters, are uninteresting. Only the recurring figure of robot psychologist Susan Calvin is drawn distinctively enough to stick in the mind after the puzzle of each story is solved.

Also these stories, considered so futuristic at one time, now have an old-fashioned quality about them. The "gee-whiz" dialogue and the quaint relationships between people spell 1950s. The stories are also dated by the lack of computers in the supposedly technologically advanced society and many other features that now seem like anachronisms.

But the stories are still diverting, if you can put aside your twenty-first century experience. Frankly, I get a kick out of them, a kick that has little to do with literary or technical credibility.

In the latter stories of I, Robot, and especially in the stories and novels to follow, Asimov writes his mysteries less to titillate with technical problems and more to raise moral questions—in particular, to address the issue of what is distinctive, if anything, about being human. While the early puzzle stories may kindle a child-like excitement, the latter stories involve the intellect more deeply.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies