Frankenstein

Critique • Quotes • Text • Frankenstein at the movies

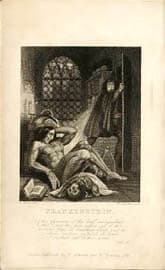

Frontispiece, first illustrated edition 1831

Frontispiece, first illustrated edition 1831Original title

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

First publication

1818

Literary form

Novel

Genre

Literary, science fiction, horror

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 78,000 words

Monstrous novel strikes a chord

By several standards Frankenstein is a very poorly written novel. The narrative wanders all over, bogging down in irrelevant subplots and extraneous characters, the characters (except for one) are thinly and erratically drawn, and author Mary Shelley seems to have no concept of dramatic development—the story continually leads up to critical points only to dissipate in anticlimactic, throwaway sentences.

But Frankenstein has three things going for it: a great idea that taps into modern fears, a great central story, and one great enduring character, the monster.

When you first approach Shelley's Frankenstein, you've got to put aside old movies and popular culture references. There's no dark castle framed by lightning. No mad scientist screaming, "It's aliiiive!". No hunchbacked Igor raiding cemeteries. No torch-wielding villagers chasing the monster.

No flat-topped, neck-bolted monster emitting inarticulate growls.

For a while there's not even a Frankenstein, as the science student of that name is not introduced until we've suffered through pages regarding the life story of Robert Walton. This fellow is captaining a ship toward the North Pole and writing letters home to his sister, until he takes Frankenstein on board and gives the narration over to him.

Then we get Frankenstein's life story, through his childhood, through his scientific studies, up to him putting together body parts which he tries to animate. How this is accomplished in his modest rooms is never explained. But the creature opens its eyes.

And what does Frankenstein do? Call his friends and colleagues to come see this incredible groundbreaking success? Sing and dance and shout with joy? No, he goes to bed. And lets his creation lurch off.

At a later point in the novel, when Frankenstein is charged in the murder of a man who was actually killed by the monster, we get a long build-up of his misery in prison and his hopeless prospects. Then, when the fateful day of his trial arrives, we're told in a singe sentence he was acquitted because he had a good alibi. And we move on to the next events.

This kind of bizarre, deadening narrative occurs repeatedly. Long droning about Frankenstein's state of mind and short shrift given to critical points of narrative. I suspect Shelley thinks the story is really about the scientist's conscience, or about his unrealistic relations with his boring friends, family and lover. To tell the truth, I was glad whenever these cardboard figures got bumped off by the monster. See, author, your story is really about the monster.

A moving murderous monster

When the monster takes centre-stage and tells his own tale (yes, he's quite articulate in the novel), we get quite a few schmaltzy and unbelievable scenes as well, but the experience of the horrible-looking creature who reaches out for companionship only to be rejected at every turn is one that can move us. We actually understand why he resorts to murder.

Unfortunately, the moral that readers and critics have taken from the story—and which Shelley clearly intends—is that expressed by Frankenstein: knowledge is dangerous, ignorance bliss.

The novel is alternatively titled The Modern Prometheus, after the character in Greek mythology who stole fire from the gods and was punished with eternal torture. This theme of course fits neatly with Christian warnings against excessive human striving and "playing God". It has been woven throughout modern culture.

When science fiction writer Isaac Asimov wrote his famous robot stories (upon which Star Trek's Data is modelled), he rebelled against this stereotype of human creations turning on their creators—he built safeguards into his creatures to present a more positive prospect and counter the Frankenstein effect. Nevertheless popular fiction has continued to exploit the fear of science progressing beyond magic, as presented in this, Mary Shelley's "ghost story".

By the way, two versions of Frankenstein by Shelley exist, one based on the original 1818 text and the other on her 1831 revision. The latter usually includes the author's introduction to the "Standard Novels Edition (1831)" in addition to the earlier preface which was written by her husband Percy Bysshe Shelley. This is the version you are most likely to find in a modern printing, though some critics claim the earlier edition is to be preferred as being harder-edged and wittier. The main story is the same in both.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Text • Frankenstein at the movies