The Shipwrecked Sailor

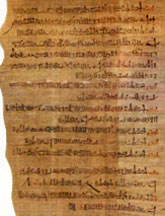

Shipwrecked Sailor papyrus

Shipwrecked Sailor papyrusAlso known as

"The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor"; "The Sailor and the Serpent"; "The Island of Enchantment"

First publication

c.1990 BCE

Literature form

Novel

Genre

Literary

Writing language

Ancient Egyptian

Author's country

Egypt

Length

Approx. 1,600 words in English translation

The original castaway tale

Here's a story so old it was "written" before the alphabet was invented. It was first "published" on papyrus. It's also so short you can read a modern translation of it in only a slightly longer time than it takes to read this article.

The story is rather simple and fantastic, like a fairy tale: Egyptian guy seeks an audience with the Pharaoh to tell him about his experience as a castaway on an island with a talkative, friendly serpent. He has gifts for the pharaoh from the serpent. The Pharaoh's screener agrees it's a good story, whether or not it's true, and lets him in.

Why care?

Well, it's kind of neat to realize this is the first example of the classic shipwreck tale to come down to us in one complete piece. It may have been the basis for the later, similar Sinbad tale in One Thousand and One Nights and possibly for some of the island adventures of Ulysses in The Odyssey, later leading to Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson,and Jules Verne's The Mysterious Island (not to mention the 2000 movie Cast Away with Tom Hanks in which he converses with a basketball in place of a serpent). Perhaps for these reasons of influence on later fiction, The Shipwrecked Sailor is one of the more popular and enduring literary works of ancient Egypt.

Translations may differ

You'll also note translations of the story vary wildly. The original was in Egyptian hieratic script, which is like hieroglyphics but sketchier. There's a lot of leeway for interpretation. Some translators render it in prose, others in poetry. I don't know how they make this choice based on the rows of symbols. I understand the old Egyptian writing employs literary devices such as puns and homonyms in the story but I'm not sure this requires poetry to translate.

Another problem is that there's a dispute over how much of the writing on the papyrus that preserves the tale (and is kept in the State Hermitage Museum at St. Petersburg, Russia) is supposed to be part of the story. If we take it all, the narrative appears to offer a framing device in which two men are returning from a failed expedition and the more senior one is fearful of their leader's wrath. To calm him, the more junior officer recounts a previous trip on which he was shipwrecked and returned to a warm welcome—a tale within a tale. Many translations however skip the frame and go right to the main story.

Even in the main story the details differ from translation to translation. For example, in some the serpent tells (in a tale-within-a-tale-within-a-tale) how he was once part of a community of seventy-five serpents on the island but then a strange girl appeared and fire from heaven killed her, as well as the other serpents. In other versions, there is no girl from outside but a star falls on the island and wipes out all the serpents except the speaker and his daughter whom he had managed to save.

Although you can read the bare text of "The Shipwrecked Sailor" online and elsewhere, you may also appreciate some of the available books, as they often include wonderful graphics that help bring the story to life—to give you a better idea of how enchanting the story must have been to folks in ancient Egypt. The Foster translation also includes the original hieroglyphics, which are fun to try to figure out for yourself. Maybe you can settle to your own satisfaction the differences over translation.

The colourful edition with the Bower prose translation is designed specifically to interest today's youngsters, though you might get a kick from it too.

The Literature of Ancient Egypt (2003), edited by William Kelly Simpson, is a standard collection of all works from this period, including "The Shipwrecked Sailor", "The Tale of Sinuhe", and The Eloquent Peasant", each rendered into either prose or poetry. Now in its greatly revised third edition, it's academically reliable but easy to read with just enough introductory notes and footnotes.

(Don't get any of these mixed up with The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, which is an altogether different castaway tale.)

— Eric