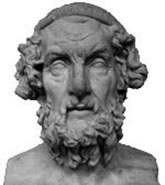

Homer

Critique

Born

c.800 BCE

Died

c.700 BCE

Publications

Poetry

Genres

Epic, historical fiction, mythology

Writing language

Homeric Greek

Place of writing

Ionia, Greece

Literature

• Iliad (c.800 BCE)

• The Odyssey (c.800 BCE)

Poems

• Iliad (c.800 BCE)

• The Odyssey (c.800 BCE)

Adventure Fiction

• The Odyssey (c.800 BCE)

Fantasy Literature

• The Odyssey (c.800 BCE)

Greek Literature

• Iliad (c.800 BCE)

• The Odyssey (c.800 BCE)

The writer who took centuries

For a poet who may not have existed, Homer has had an awesome influence over the past three thousand years.

When we speak of "Homer", we're referring of course to the author of the ancient Greek epic poems about the Trojan War and one warrior's journey home from the war, respectively Iliad and The Odyssey, which every schoolchild has studied—or at least has seen depicted in movies and on television. They're the most enduring legends known to the Western world, rivalled only by the stories of the Hebrew Bible.

If such an individual as Homer did exist, he probably lived in a Greek colony on Asia Minor (Turkey today) around the ninth or early eighth century BCE, though some think he can be placed as far back as 1200 BCE, shortly after the purported war of which he sings.

The problem is, between these dates the eastern Mediterranean world was in somewhat of a dark age. The people of that era looked back at the time depicted in the epics as a golden era (which was actually the Late Bronze Age, according to archeologists), as a period of great political and social organization, of economic and military might. It was also said to be a time when gods had walked among people, many of whom were semi-divine themselves. As the Greek world recovered from ruin and started rebuilding its culture—and power—people were heartened by fables of their former glory. The Homeric tales were shaped to this end during the recovering centuries.

Oral history

We don't know if the originator of Iliad was the same person who first composed The Odyssey. Or if either poem was even created by a single person. Both works may have been created, revised and expanded by many hands. Some scholars argue each of the two major poems must have been brought together from numerous existing poems by a single poet, shaping it into the epic, probably around 775 BCE. The evidence for this lies in the consistency of each work's poetic expression.

Another line of research places the inspiration for these stories, even further back to the Indo-European language speakers of Central Europe and the Steppes of Asia who spread over Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East and northern India as far back as 4000 to 3000 BCE. Their influence explains the correspondences among the mythologies of many early civilized peoples, including the Greeks.

But in any case, it is generally doubted that Homer, or anyone else, wrote either of the epic poems associated with his name from the beginning. The people who became the Greeks had been literate in the golden age but they'd lost that facility in the dark years. In the oral tradition of the intervening time, these historical poems, which recalled that earlier time, would have been committed to memory and recited (chanted or sung, actually) at gatherings by storytellers, with additions made over several centuries. Among the evidence for this is the fact that the poems contain a number of gross anachronisms, with devices and practices from the dark ages inserted into the story that supposedly took place centuries earlier.

The recovery of literacy by the Greeks in the eighth century BCE coincides with the period in which, it is speculated, one man—"Homer"—wrote down the Iliad with a singular poetic vision. Even after the story had been committed to writing, however, it continued to be presented orally for two or three hundred years, with many revisions undoubtedly creeping in. Our knowledge of the written text comes from a surviving later version, after more oral presentation shaped it further, rather than directly from what had been put down by the presumed Homer.

Whether after the Iliad the same man went on to write The Odyssey is a matter of additional conjecture. Some scholars point to differences in the epics regarding attitudes towards the gods and to differences of style to argue for distinct authors. The Odyssey seems to them more likely to be the work of a slightly later poet who put the Ulysses stories together with knowledge of the Iliad as written by Homer.

So, when we continue to refer to "Homer", it should be understood we're talking not necessarily about a particular individual but about the poets and performers that shaped two of the world's greatest myths over several centuries. In effect we're talking about the ancient Greek people.

Not that they even considered themselves Greek then. Their loyalties were to small kingdoms and cities. Part of the appeal of the Homeric poems was that they heralded the transition of the inhabitants of the area into a wider awareness of themselves as a people. Like all mythologies important to a people, the stories of the Iliad and the Odyssey encoded the people's fears and aspirations as they began to feel their collective power.

It's what you value

Why do we still care today? Well, to a large degree we don't. We've absorbed the imagery, we refer to Homeric characters and situations in our language (often without realizing it), and our writers plunder the epics for good storylines in modern entertainments. But most of us don't dwell on the details of the myths as ancient Greeks did. We don't feel the fates of Achilles, Agamemnon, Helen, Hector and Ulysses are significant in our daily lives.

But Homer's works are still significant to our civilization as a whole. And anyone who immerses oneself in them can still come away with a sense of having been involved in something meaningful. Why is this?

Homer has been called the Shakespeare of the ancient world, and if you've read my views on Shakespeare, you'll have a good idea how I look at Homer's writings. In short, I think we appreciate him in proportion to how much the values he promulgates are still relevant to us.

Homer was writing not only as the Greek world was developing—onde of the first societies we give the word "civilization" to—but also as the pattern for the Western world was being set. We find early templates for ideas of the common good versus the power of the individual. The pitting of mortal strength against fate and the gods. The obligations of men to their leaders, of women to their men, of children and their parents to each other. The right of might and the nobility of blood. It's all delivered as an enthralling story for its time and honed as entertainment, but one can read (or listen to) Homer as a series of morality tales, as guides to how one should behave in the new world coming into being then—to a large extent, our world.

Of course, the morals of the stories are not always what we would consider helpful today. On those counts, Homer is not relevant enough to grab our imaginations. But in those aspects of the adventures that do still reflect our society and lives—what we think of as the "universal" themes—we can still be engaged.

So my advice is to read Homer for the fun of it and if you give in to the sprit of it you'll automatically pick up on what is still meaningful to us today.

Try to imagine what it would have been like in an age without television, movies or even books, to hear these stories in person as they rolled out in thunderous and portentous phrases. Imagine yourself huddling with others in the dark, listening to the voice beside the fire but following with your imagination the exciting tales of men fighting for their honour and for their lives against each other, against the elements, against barbarism, against the gods, against monsters within and without.

— Eric

Critique