A Rose for Emily

Critique • Quotes

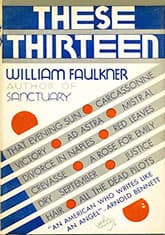

First edition of collection, 1931

First edition of collection, 1931First publication

1930, in magazine Forum

First book publication

1931, in collection These Thirteen

Literature form

Story

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 2,900 words

Entry-level Faulkner

Critics find in William Faulkner's story, "A Rose for Emily", an allegory about the American South living in the past, decades after the Civil War, still holding on to the dreams of a supposed former glory, morbidly embracing its decadence. Something like that.

And there is some of this in the story. There's some of it in nearly everything Faulkner wrote. It's the backdrop to all the tales he tells about the people of his fictional town in Mississippi.

The narrative outline of A Rose for Emily would certainly seem to place it in the category of Southern Gothic writing. Emily Grierson is the last of a once aristocratic family after her father dies. She refuses to pay her city taxes and becomes a hermit in the house she can no longer keep up. When she eventually dies herself, the town recasts her in memory as a beloved eccentric—until a macabre discovery is made.

It's been described as Mark Twain writing "The Fall of the House of Usher". Smalltown gothic.

But I'm not sure you have to understand the allegorical details, all the alleged symbolism, the full historical and social background, to appreciate the human story here.

I could imagine a similarly dark story being told in completely different contexts—say, in New England by Stephen King, or in the American Midwest by Willa Cather, or in Canada by Alice Munro (whose writing has been called Southern Ontario Gothic). Or anywhere you have solitary older people living in the past, guarding their tragic secrets from the community. Though with a somewhat different kind of ambience.

Foreboding and claustrophobia

Faulkner's details are drawn from the experience of living in a particular place, made obvious with the references to such Southern touchstones as the Confederacy and northern carpetbaggers. He quickly draws the minor characters—the politicians, the local minister, the black servant who keeps the aging lady's secrets, the interfering distant cousins—to swirl around, without resolving, the central mystery which is Emily. There's a great episode when townsfolk are upset about a strong odour apparently coming from her rotting house but, not having the nerve to risk offending the lady about it, the town council sends men in the dark of night to spread lime about the property.

How Faulkner writes "A Rose for Emily" enhances its foreboding quality. Most of the story is told from a rare first-person-plural perspective—by a "we" that seems to be the town itself, lending a claustrophobic feeling to the tale.

The story starts near the end with Emily's funeral and then jumps back to laying out the narrative leading up to it, selecting the order of events in her life—as witnessed by the town—that contribute to building the image of her strangeness, building the mystery.

Time-disordered narratives can be annoying, making a work appear disjointed and hard to follow, but Faulkner's skill is such that "A Rose for Emily" goes down smoothly. It never seems convoluted but always natural—right up to that surprise ending.

Along the way, large and small mysteries are hinted at but never solved. What really happened with Emily's father? Why did she delay acknowledging his death? Did her northern lover really return to here? Did she poison him? Why? Was he going to leave her? We have "probably" answers to these questions but never certainty. And yet the story still seems complete.

It helps that in this early story Faulkner does not use the stream-of-consciousness style known from his novels. There are no pages-long paragraphs meditating on fine gradations of emotion and intellect. Literary experimentation is tightly controlled to efficiently stitch together what is known of one reclusive woman's life.

This makes "A Rose for Emily" an easy read, compared to other works by the author. It's an entry-level Faulkner story, with enough of his gothic overtones and eccentricities to introduce you to the author's oeuvre but without turning you off altogether. It's been called a "gateway drug" for readers who may become Faulkner addicts.

Personally, William Faulkner is not my literary drug of choice. But this story is a rush.

The N-word

Some have called "A Rose for Emily" one of the greatest American short stories ever written, maybe the greatest.

The use of a certain derogatory term for blacks, though, has cast a pall over the story's reputation in recent years. One may excuse the expression, which appears exactly four times, on the grounds that it would have been commonly spoken at the time of the story, particularly in the southern town. The word "Negro" is used another thirteen times in the story, indicating Faulkner resorted to the more offensive term not out of a personal animus but only when it seemed to be the word that would naturally have been used.

But comments made by the author in later life have created qualms about the man's actual, complicated views on race—and their possible subtext in the story.

Quoting from "A Rose for Emily", some critics have substituted "Negro" for the offending word and you may find this revised text in some online sources.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes