The New Testament

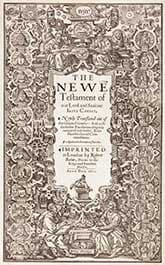

Title page in Gutenberg Bible, 1611 folio

Title page in Gutenberg Bible, 1611 folioFirst publication

c.48–110

Literature form

Prose and poetry

Genres

Religion, history, mythology, biography

Writing languages

Koine Greek

Authors' places

Greece, Syria, Palestine

Length

Approx. 188,500 words (King James Version)

What's great about the world's best seller?

It's often called "the greatest story ever told". But is The New Testament—or more precisely the gospel story within The New Testament—even one of our best stories?

Of course, when they make that "greatest" claim, Christians are usually judging their founding story for its religious messages. And why not? Taking the scriptures at face value—believing in it as the word of the universe's creator, as divine guidance on how to live, achieve immortality and triumph in the coming apocalypse—well, that's got to make it the most important text ever. For them, that is.

As with The Old Testament, however, we are not considering this volume as theology but as creative literature comparable to other ancient literary works.

So, among the greatest? On a couple of criteria, maybe.

First, longevity. The books of The New Testament have endured in the public imagination for nearly two millennia, placing them on a pedestal alongside other very old books that are still revered. Arguably higher than those other tomes. It's undeniable far more people have Bibles in their home today than possess copies of Iliad, The Odyssey, Gilgamesh, Aeneid or any other work of the ancient world.

The early days

A skeptic could charge with some justification, however, the Bible has remained prominent among literature for so long only because it's had Christianity, the world's most successful religion, behind it. But one could also argue cause and effect run the other way: Christianity has only reached its peaks of success because of its basis in The New Testament.

The text and the church developed together in the religion's early days. The New Testament's four gospels (attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) can be rearranged in historical order (Mark first) to show the evolution of the Jesus story and its growing appeal to an audience beyond its Judaic roots. The subsequent books—Acts of the Apostles, the Pauline and other letters—continue in this direction, providing advice on how Christians should behave, what they should and should not believe, in order to build the church that became the world-leading institution known to history.

Does the enduring popularity of the book and the religion make The New Testament great literature? Not necessarily, but it helps.

Another factor often mentioned as showing the literary greatness of The New Testament is its influence on other literature over the centuries. The Bible has provided innumerable stories that have been retold, added to, or satirized. In The New Testament, Jesus's well-known parables—the good Samaritan, the prodigal son, the lost sheep, and about forty more lessons in story form—have been particularly fruitful sources for other storytellers to pick up, either for full reworking or for reference as passing metaphors.

Western literature ever since has been full of references to New Testament incidents it is assumed everyone knows: Christ turning water into wine, the sermon on the mount, Judas's betrayal, Pilate washing his hands, Saul's conversion on the road to Damascus, the four horsemen of the apocalypse, a multitude more.

Our everyday language has been inundated with expressions we might not realize came from the latter scriptures: "baptism of fire", "pearls before swine", "eat, drink and be merry", "wolf in sheep's clothing", "cross to bear", "millstone around the neck", "turn the other cheek", "move mountains", "blind leading the blind", "many are called, few are chosen", "he who lives by the sword dies by the sword", "the truth will set you free", "a law onto themselves", "fall from grace", "reap what you sow", "money the root of all evil", "Armageddon"....

Straight to the heart

It may again be protested these effects of The New Testament are due more to the domination of the Christian religion in Western culture, than to the inherent literary qualities of the text. And this may be fair. But at least the stories and expressions presented in the religious scriptures are striking enough to be taken to heart by the culture. That counts for something in the literary stakes.

Parables are presented in The New Testament precisely because they are memorable little fables that can be understood on several levels. The narrative-driving incidents, especially in the gospel tellings of Christ's life and death, are there to engage readers and listeners—more than could any dull recitations of events and injunctions to be righteous without these stories. The language, whether found in the original Greek or enhanced by later translators, is picturesque to entertain us. These are all features of creative literature.

Not that The New Testament is all clever stories and catchy language. It can be repetitive, obscure, self-contradictory and dull in long stretches. Much of the text has to do with arcane issues of doctrine in the early church.

It's not as boringly bad as The Old Testament, mind you. For one thing, The New Testament is much shorter, less than a third the length. It has fewer of those lists that fill the older pages of the Bible, all those genealogies, census figures, and detailed instructions for offerings and sacrifices. And the newer volume has little, if any, of those divine demands, threats, punishments and outright massacres that make The New Testament one scary book.

Don't get me wrong, The New Testament is not all love and peace in opposition to the The Old Testament, as it's sometimes portrayed. And the hallucinogenic book of Revelation, which concludes The New Testament, hearkens back to the older books in its nightmarish visions of a God taking bloody vengeance on the majority of humankind while saving his most ardent worshippers. But the relative positivity of the gospels can be a relief for anyone who struggled through the earlier dark testament.

Same story from different angles

As for The New Testament's repetitiveness and contradiction, I'm of several minds.

Take the gospels, three of which (Matthew, Mark and Luke) present similar but not identical biographies of Jesus, and the fourth (John) offering a very different take on it, not to mention Acts adding a few more details. The church making them all canonical scriptures is obviously an attempt to impress upon early Christians the truth of their foundational story. At the same time, the apparent sloppiness in editing them together gives skeptics the chance to pick out inconsistencies—showing the stories are inaccurate at best, untrue at worst. They also let scholars illustrate the evolution of the depiction of Christ and his messages through The New Testament, implying an historical development rather than a straight presentation of the absolute word of God.

But let's ignore the historicity issue and consider The New Testament just as a creative work of literature. Then we can appreciate this work of art featuring several large chunks of text telling the same story from different angles as an interesting literary choice. You can see it as a modern or even postmodern technique. Raising issues of relative viewpoints and unreliable narrators. Forcing readers to play detective, evaluating clues of plot and character. Why does this Jesus fellow imply here he's just a prophet but claim there he's a god? Is Christ really saying the only way to heaven is through belief in him or does he insist you also have to be poor and do good deeds? What is Judas's real motivation or is he unfairly depicted? What do the varying accounts of whether or how Christ appears to others after his death tell us more about the expectations of different narrators? What struggles are going on among the characters in the story and afterwards over how best to present the Christian messages?

Of course we know the Bible's authors weren't making their storytelling choices in order to present an engaging literary mystery for us. That's just something that the process of separate writers working on their own stories—and editors putting together all the seemingly worthy stories—ended up creating. Moreover, most Christians are not really aware of the contradictions in the books of The New Testament that result from this process. They just dip into whatever section they're directed to at various times and seek their inspiration wherever they find it.

For those of us reading the Bible as literature, as we would any prose narrative or epic poem, The New Testament isn't bad. Maybe not as great a mythological tale as other ancient works. Maybe not as compelling as many a modern masterpiece, nor as intriguing as many a postmodern fiction. And certainly not the greatest story ever told.

But it's up there, among the complex and interesting works of myth and half-remembered history that have widely affected us and our literature.

An accolade I don't expect to win me any points with either believers or skeptics.

— Eric