Beowulf

Critique • Quotes • Text • Translations • At the movies

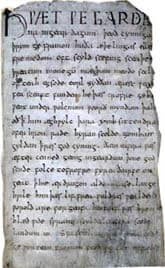

Earliest known manuscript

Earliest known manuscriptFirst publication

c. 700

Literary form

Poem

Genres

Literary, epic, mythology, adventure

Writing language

Old English

Author's country

Unknown

Length

Approx. 30,000 words

The original spine-tingler

It wasn't called Beowulf until 1805 and was not printed till 1815, more than a millennium after its appearance in manuscript. But to early Anglo-Saxons, the slaying of the monster Grendel and Grendel's mother by the hero Beowulf was a tale more spine-tingling than anything Stephen King or Steven Spielberg could come up with today.

Despite the work being known as an English classic and it having been put into literary form in Christian England in the seventh century, the tale actually takes place in pagan Scandinavia and northern Europe, where it likely originated. It does not mention England at all.

The story tells of a young Beowulf, whose name probably means something like "bright wolf" or "noble wolf", although some researchers propose etymologies that range from "bee-hunter" to "woodpecker". In any case, Beowulf is a semi-historical figure who possibly did win a kingdom in what is now southern Sweden during that period of transition from ancient times to the early Middle Ages, often misleadingly called the Dark Ages.

In fiction Beowulf is an heroic character who achieves fame by killing a monster (something like what would later be called a dragon) in a foreign king's court. Later he goes after and slays its revenge-seeking mother in an underwater lair.

Still later, in a lesser-known continuation of the epic, the story jumps ahead fifty years, after Beowulf has ruled his own kingdom for all that time and when he finally faces a new monster threatening his people. The conclusion of this battle is more tragic—and not just for the monster. A number of other epic stories are also woven into the poem.

The original literary form of Beowulf is Old English heroic epic poetry, meant to be sung or chanted to simple musical accompaniment. Each line is divided into two parts that are united by alliteration and similar stresses. Some translations into modern English preserve these characteristics while others take a freer approach.

You can even find Beowulf translated into straight prose. Although this may strike the modern eye as easier to follow, I recommend a good verse translation that retains the alliterative poetry. It takes some getting used to but once you reach that point you'll find the sound and rhythm of this poem will carry you along swimmingly. There's a reason this work is revered, apart from it just being old.

Where's the monster?

What's the meaning of Beowulf—what should we get out of it? Various academic theories concern the saga's place in the world of its origins, having to do with depicting the warrior code of that age, the relation of lord to vassal, the importance of kinship and nobility, even the struggles of Christianity to assert itself over monstrous heathen beliefs. And there is much to those interpretations.

But I prefer to see it in terms of what has made the story relevant, fascinating even, to readers over the centuries. It's the age-old story of courage to confront the forces of darkness, to defeat the devils both within and without us to gain a brighter future.

This is not to say it's a one-sided story of pure heroism. Part of the attraction of Beowulf is that the hero is flawed, at least as we see him today, leading to the oft-forgotten ending—exemplifying the classic definition of tragedy. And the monsters of the piece are varied, with different motivations that elicit occasional empathy. Nor are the people, on behalf of whom Beowulf fights, completely innocent. In this story of light versus darkness, grey dominates.

Which may be why Beowulf has never been adapted for a really crowd-pleasing, feel-good movie, but explains why we keep going back to it to try to understand this part of our heritage.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • Text • Translations • At the movies