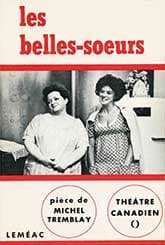

Les Belles-Soeurs

Critique • Quotes

1972 edition

1972 editionFirst performance

1968

Literature form

Play

Genres

Comedy

Writing language

French

Author's country

Canada

Length

Two acts, approx. 16,000 words

Entertaining misery

How does Les Belles-Soeurs maintain its international popularity as a progressive play several decades after first hitting Quebec theatre?

In 1968, Michel Tremblay's drama was recognized as game-changing for featuring an all-female cast speaking the dialect of Canadian French known as joual, the gritty common tongue of Montreal's working class. Since then, the play has been translated into the vernacular of many other languages and presented on stages across Canada and other countries.

When you read Les Belles-Soeurs now, at least in English, the dialogue may seem ordinary, the everyday language we've become used to hearing in movies and on television. The disrupting impact of first hearing it in the cultural environment of its time is not to be felt again.

Of course, it's not just the language that once made Les Belles-Soeurs seem revolutionary. The focus on the lives of working-class women, poor housewives obsessed with futile consumerist dreams, must have been startling.

Imagine a playwright trying to sell the concept to producers then. A dozen women sit around in a tenement sticking grocery store stamps in booklets that can be exchanged for products: furniture, appliances, stereo TVs, nylon carpets and, as million-stamp winner Germaine says, "those Chinese paintings I've always wanted, the ones with the velvet". With rare interruptions from the outside world, they discuss the pains and small comforts in their lives, which revolve around men, the church and the latest gossip. Every now and then, like their own chorus, they break into surreal choreographed recitations—such as when they rhapsodize over the biggest joy in their dreary existence: Bingo.

Cultural relic

Despite this unpromising summary—and despite the initial bemusement of critics—Tremblay's play has proven enduringly popular. Successful debuts and multiple revivals of Les Belles-Soeurs have taken place widely. (I happened to catch its opening night in 2023 at Stratford, Ontario, where it met with gales of laughter and a full-house standing ovation.)

A film adaptation is also planned. It will be interesting to see if or how a cinematic version opens up the play's events beyond a single evening in a Montreal apartment.

But it may also be interesting to see how the drama is updated. For, despite the play's continuing appeal, it's hard to shake off the feeling Les Belles-Soeurs is a relic now.

Supporters may insist the play is as relevant now as fifty years ago. It shows women dominated by men, ruled by religious morality, at the mercy of large economic forces—and forced into narrow existences of consumerism and trivial pursuits. A legacy not entirely behind us today.

And, to be fair, Les Belles-Soeurs often plays more like a light-toned comedy than the tragedy our grim critique makes it sound like. The audience is kept entertained.

Unraised consciousness

But under the wisecracks and laughter yesteryear's women of Les Belles-Soeurs are beaten. Rather than joining together to change their status and challenge the system that oppresses them, they put their remaining energies into interpersonal disputes. They browbeat each other, abuse elders, enforce conformity and ultimately cheat each other, which seems to be the point of the play.

I won't repeat a rape joke told at one point. (Surprisingly left in the production I saw recently, eliciting embarrassed guffaws.)

Yes, this may be a depiction of a reality in certain circles at a certain time and place—just before Quebec's secular Quiet Revolution took hold in the 1960s.

But this was also the period when women's lib, as it was called then, was developing. It was the beginning of feminist consciousness-raising as a cultural phenomenon, with books and movies encouraging women to share their struggles to break through barriers.

It might have been unrealistic to show the particular women of Les Belles-Soeurs joining together to reject their oppression. Perhaps the play is just a sad commentary on the lot of women at a certain point in time. But you might still expect the women in such a play to hint they have at least an inkling about someday breaking free of their situation, at least a consideration of other ways of living being possible.

Even if we give Les Belles-Soeurs the benefit of the doubt as a play firmly ensconced in its era, continuing today to wallow in these women's pointless, unhappy lives hardly seems productive—or even entertaining—today.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes