The Accidental Tourist

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1985, United States

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 125,000 words

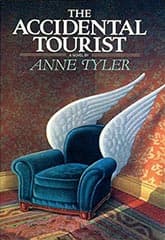

Settling into the winged armchair

Some covers of The Accidental Tourist feature an armchair with wings, inspired by the logo on travel guidebooks written by the novel's protagonist.

But there's two ways of interpreting that striking image. In Anne Tyler's novel it's meant to suggest travelling without leaving the comforts of home, as preferred by travel writer Macon Leary (yes, that's really his name) and his readers. His paperback series offer tips for travellers who don't want the bother of experiencing anything different from their normal existence. An allegory no doubt for going through life protected from the world. Macon's life, specifically.

But if you came across the winged armchair image before reading the novel, you might take it differently—as experiencing life without leaving home. Perhaps curling up in a comfy chair with a book to see the world in imagination without physically going anywhere.

This impression can also apply, if perversely, to The Accidental Tourist. For here is another novel of upper-middle-class angst that doesn't really go anywhere of any profound significance. It's the kind of story that gets over-praised for being character-driven because there's not much of a plot beyond the joining and separating of characters.

The messy world of people

To be fair, Tyler is adept at creating characters that do "go somewhere"—that is, characters who develop. Their changing mental lives, relationships, and positions in society become the plot.

Most obvious is the evolution of Macon Leary. He starts as a highly controlled man who obsesses over practical details of daily life for his travel books and walls himself off from the messy world of others, submerging his grief over the death of a son and the dissolution of a marriage.

He gradually crawls out of his shell under the influence of the second most important character, Muriel Pritchett, who starts as his dog trainer and draws him into her chaotic world. She's the spontaneous, perceptive girl-woman, a counterculture type who barges into his life and rejuvenates him—while moving in the opposite direction herself, struggling to establish a more stable life.

Macon's wife Sarah is the least developed of the three main character. She's another type, the conventional wife who cannot understand her husband enough to help heal their relationship.

The working out of these relationships makes for a passing entertainment but I don't know what more to make of it. Not because The Accidental Tourist is difficult—Tyler is a clear, engaging writer—but because there's so little here to make anything of. More anxiety over nothing in particular, except that people are strange, understanding is elusive.

It also fails to address more basic issues of society that might give rise to these disconnected feelings. Macon's obsessive eccentricities are never shown as related to any kind of social or cultural failure. They're just odd, personal, even laughable, quirks of character.

Alienation of the sexes

While first reading The Accidental Tourist, I couldn't help noting certain comparisons to John Updike's novel, Rabbit, Run, which I had read earlier. Both focus on alienated male figures. Men discontented with domestic life, suffering existential crises, unable to sustain connections. Resorting to flight.

This seems to be a bit of a pattern in latter twentieth-century writing, maybe as an answer to the more prevalent stories of women escaping stultifying relationships.

Tyler and Updike are very different writers, of course—Tyler's prose being far less textured, her humour far lighter, her sexual relationships far less sordid. Both are writers finding drama in everyday life, though Updike's work is all gritty modernism, while Tyler's is quirky, often placed in the category of domestic realism.

Their lead characters' journeys are also quite different. Rabbit Angstrom' selfish, impulsive man-child seeks freedom from responsibility but eventually—grudgingly—faces up to it. Macon Leary is a control freak seeking protection from life's pain and unpredictability but eventually comes to live with it, more or less happily.

One character's journey leaves you, the reader, somewhat unsettled at the end, unsure whether an ultimate resolution has been found. The end of the other character's journey leaves you with the literary equivalent of a hug.

Macon Leary is never forced to examine the source of his behaviour or learn to change it. Rather, he finds refuge with someone who accepts him with all his weird habits and helps protect him from the real world. This should be disturbing but instead the ending is presented with the warm reassurance that all has worked out as Macon could wish without having to face the unpleasant effort of truly trying to understand himself or the world.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes