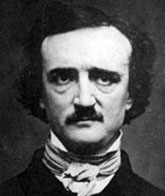

Edgar Allan Poe

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

Born

Boston, Massachusetts, U.S., 1809

Died

Baltimore, Maryland, U.S., 1849

Publications

Stories, poetry, novels, criticism

Genres

Literary, fantasy, horror, adventure, science fiction, crime, mystery

Writing language

English

Place of writing

United States

Literature

• Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839)

• "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

• The Raven and Other Poems (1845)

Stories

• "The Man That Was Used Up" (1839)

• "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839)

• "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

• "A Descent into the Maelström" (1841)

• "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1842)

• "The Gold Bug" (1843)

• "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843)

• "The Purloined Letter" (1844)

• "The Cask of Amontillado" (1844)

• "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" (1845)

Story Collections

• Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839)

• Tales (1845)

Poems

• "The Raven" (1845)

• "Annabel Lee" (1849)

• "A Dream Within a Dream" (1849)

American Literature

• Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839)

• "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

• "The Raven" (1845)

Adventure Fiction

• Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838)

Crime and Mystery Stories

• "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841)

• "The Gold Bug" (1843)

• "The Purloined Letter" (1844)

Fantasy Stories

• "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839)

• "The Masque of the Red Death" (1843)

• "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843)

• "The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" (1845)

Horror

• Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839)

Horror Stories

• "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839)

• "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842)

• "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1842)

• "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843)

• "The Cask of Amontillado" (1846)

Science Fiction Stories

• "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" (1835)

• "The Man That Was Used Up" (1839)

The seriously sick artist

It's hard to take Edgar Allan Poe seriously as a literary figure.

Not his fault. Poe took writing very seriously as an art form. His critical works show this. And his stories have proven tremendously influential in both the literary world and in popular culture.

Ah, yes, but about the culture. All those schlocky movies that have been adapted from his works. The horror clichés that have grown up to practically hide his complex concepts of the grotesque. The mystery and detective stereotypes that have obscured their origins in his fiction.

And the bloody parodies, conscious or otherwise. People who have never read a word of his can cite "Quoth the raven, Nevermore" from cartoons and associate whole genres of entertainment with decaying mansions, mad recluses, torture pits, and bodies in the woodwork.

Not to mention the myths enveloping Poe's life. The common conception of Poe is of a drugged-out wastrel who lay about having grisly nightmares, which he wrote down in paranoid prose and poetry, until he eventually succumbed to madness himself.

Actually the cause of his death is still mysterious, with theories including alcoholism, various diseases, and manslaughter. But there's little evidence he was addicted to drugs. And there's plenty of evidence he worked very hard at—and thought very deeply about—his craft.

His first craft was poetry. His tumultuous youth ranged among Boston, Scotland, London and Richmond, Virginia and his early experiences included the loss of both parents, being adopted, a failed university career, a lost love, and a stint in the United States army. But throughout his adolescence he wrote poems, leading to his first publication when he was eighteen. The most enduring of those early efforts was the epic "Tamerlane", first published in his 1827 poetry collection. His first book's run of fifty copies were ignored at the time but today are pricey collectors' items.

In his early twenties he turned to prose and found limited success by publishing stories in northeastern U.S. periodicals. In 1833 an early story of a sea disaster, "MS. Found in a Bottle", won him some attention by winning a contest in a Baltimore publication. Many more short works followed in magazines and newspapers, including the similarly themed sea adventures "A Descent into the Maelström" (1841) and "The Oblong Box" (1844), along with his only novel, the more fanciful The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. Related to these are his fantastic tales, like "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" about an amazing balloon flight.

As with much of Poe's work during his lifetime, most of his bizarre adventure tales had little public impact, with critical reactions ranging from neglect to derision. However, they impressed and influenced a wide range of writers who later became prominent in both mainstream and genre literature, including seminal science fiction writers Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, poet Charles Baudelaire, fantasist H.P. Lovecraft, fabulist Jorge Luis Borges, and novelist Herman Melville, who is thought to have incorporated ideas from several of Poe's narratives in Moby Dick.

It's odd to read those stories now along with the comments of the time. What then seemed to some critics like clumsy, needlessly gory writing appears now as, yes, quirky, but well-constructed narratives from a brilliantly lively imagination. Perhaps somewhat dated and overheated—but only because they have been succeeded by a century and a half of fiction that developed the same themes in times of more understated melodrama.

Inventing the mystery

Same thing can be said about other genres with roots in Poe's stories. His famous story, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (whose length may qualify it as what some call a novelette), introduced the ratiocinating detective C. Auguste Dupin. The amateur sleuth returned in the inferior "The Mystery of Marie Roget", a dry report on a murder mystery, and the much livelier "The Purloined Letter". Along with "The Gold Bug", a tale of code-breaking and treasure-hunting that became Poe's most popular story, these works practically invented the mystery field. It is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine Arthur Conan Doyle's analytical Sherlock Holmes, Agatha Christie's incisive Hercule Poirot or any of the hundreds of fictional sleuths of our time without Poe's groundbreaking precursors.

Again, some of these stories read a little ponderously at times, because they have been surpassed by more swiftly moving and more cleverly twisting mysteries. But for the most part they are still interesting—and great fun. In an intellectual kind of way.

The group of stories that suffer most from the passage of time may be those Poe is most known for: the so-called horror stories, which were gathered in Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque (1839) and later collections. Some are still well-known today: "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839), "The Masque of the Red Death" (1842), "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1843), "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1843), "The Black Cat" (1943), "The Premature Burial" (1844), "The Cask of Amontillado" (1846)—most of which involve some kind of horrible death, torture or entombment.

Don't get me wrong. These are not bad stories. It's just that you may have the reaction after reading any one of them—reading it, not watching or listening to an adaptation—of "Is that it?" The murderer feels guilty, so he confesses? The hero is freed from a slow death at the last minute?

Part of such disappointment may be attributed to our need for endings. Poe was more interested in creating an atmosphere of apprehension building up to terror in as short a story as possible, without regard for how to conclude it. His endings are often tacked on or missing altogether. In dramatic parlance, Poe is all about the rising action to a crisis, with little or no falling off and climax.

Poe is sometimes incorrectly quoted as saying, "A short story must have a single mood and every sentence must build towards it." But he did express similar sentiments in other words. The skilful short story author, he wrote:

having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents—he then combines such events as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect. If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step. In the whole composition there should be no word written, of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design.

Exhuming the terror

In his so-called horror stories, Poe demanded that every element of the story must contribute to inducing his intended disorientation in his readers. His ideas of the "grotesque" and the "arabesque", as in the title of that first story collection, have been debated but they seem to me to have something to do with a psychological ornateness or complexity that lures hidden emotions to the surface. The most primal of these buried responses is, of course, terror.

Modern treatments of his works, however, tend to dilute his single-minded pursuit of the intended response by elaborating the meagre plots with extraneous devices and multiple twist endings.

Many of Poe's stories don't fit into any of these groupings. They're romances of a sort ("Eleonora"); they're humorous little morality tales ("The Business Man", "The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether"); they're satires on other writers ("The Devil in the Belfry", "Never Bet the Devil Your Head"); they're even satires on himself ("How to Write a Blackwood Article").

But what made his name toward the end of his short life was, after everything else, poetry, which he had continued to write. Namely, he became known as the author of "The Raven" (1945), a poem that is similar to his ominous suspense stories, building a atmosphere of dread and guilt over a back story that we never really learn. The poem made a sensation with the public and with at least half the literati—the other half loathing it as a rhythmical exhibition of cheap and childish effects.

Say what you will about its technical achievement, its cheap and childish effects do seem to work. It's one of a handful of poems that everyone seems to know a few words of. If anyone tells you they can recite one old poem, their next words are likely "Once upon a midnight deary, while I pondered, weak and weary...."

After a century and a half, literary success like that has got to be taken seriously.

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes