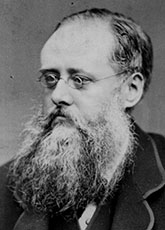

Wilkie Collins

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

Born

London, England, 1824

Died

London, England, 1889

Publications

Novels, stories, plays

Genres

Literary, mystery, suspense

Writing language

English

Writing place

England

Literature

• The Woman in White (1860)

• The Moonstone (1868)

Novels

• The Woman in White (1860)

• The Moonstone (1868)

Stories

• "A Terribly Strange Bed" (1852)

British Literature

• The Woman in White (1860)

• The Moonstone (1868)

• The Black Robe (1881)

Crime and Mystery

• The Woman in White (1860)

• The Moonstone (1868)

Fantasy Stories

• "A Terribly Strange Bed" (1852)

Horror Stories

• "A Terribly Strange Bed" (1852)

Thrillers

• The Woman in White (1860)

Author provocateur

A case could be made for Wilkie Collins as one of the most influential writers of his era, his impact still being felt today in every kind of popular fiction. As much as, or more than, the iconic mid-Victorian figures of Dickens, Thackeray and Eliot.

The argument would go something like this:

First, look at his most famous novels, especially that decade's run of extraordinary works—encompassing The Woman in White (1860), No Name (1862), and The Moonstone (1868)—which at the time surpassed in popularity even those of his friend, mentor and sometimes collaborator, Charles Dickens.

Second, consider his other major writing from this period—especially, the long novel Armadale (1866) and the socially provocative novel Man and Wife (1870)—as well as his work for several years to follow his miraculous decade. It was in some respects too far ahead of its time for nineteenth-century readers. In their day, some of his stories were thought too sensational in their narratives, too scandalous in the relations of their characters, and too propagandistic in their reformist zeal. Read today, these novels and stories may not exactly be enduring classics, but neither are they so shocking—as we have come to accept such qualities in our literature.

Third, give Collins credit for being more experimental with his storytelling techniques than most of his contemporaries. He shifts points of view among his characters and tells parts of their stories through letters and other documents (early examples of epistolary narrative). Instead of periodically bringing a tale to a halt to describe and flesh out players, he characterizes them quickly and lets them develop in the readers' minds as they interact with people and events. These are all techniques other writers have picked up on and used to this day.

The fourth and most compelling line of argument though is that Collins made enticing, intriguing stories central to his writing. Having clever, interconnected plots drive his works makes them the forerunners of modern popular writing: intrigue, mystery, horror and social exposé.

Let's not be patronizing about it though—we're not talking just about superficial bestsellers. Okay, we are talking about superficial bestsellers. But we're also talking about many of our greatest modern literary works that have found wide readership. We have Collins to thank for much of this, as much as or more than others of his time.

Consider almost any work of Dickens and you'll find marvellous characters brought together by slowly developing narrative structures. For readers today, the temptation is to skim through many of those pages to find "what happens next". Collins's characters may be less memorable, but their lives are beset by conflict, twisting fates, sudden reversals and bewitching mystery. Today it seems obvious the ideal for a writer is to strive for both: great characters in a great, involving story.

Shock and aha!

Collins's first published novel, Antonina (1850), is a floridly written historical novel of the Roman Empire that's deservedly forgotten today, along with his early memoirs, travelogue and short fiction.

But his second published novel, Basil (1852), shows the early development of his style that was to flower in his masterpieces. Basil has the mystique, the teasing style, the shifting points of views, and some epistolary narrative. Most of all, it has the (then) shocking subject matters of sexuality and adultery. The rhythms may be off, some of the plot twists may be a little awkward, and the revelations solving the mystery perhaps come too quickly and easily. But you can see Collins is on the way to developing what would become known as sensation fiction.

Around this time, he was also knocking out short stories, often for Dickens's Household Words periodical. One of the most noteworthy is "A Terribly Strange Bed" (1852), a horror story worthy of a less hysterical Edgar Allan Poe. A longer work in this vein is "The Yellow Mask" (1855), a short novel featuring a man haunted by his dead wife, although the supernatural elements are balanced by the search for a rational explanation. Again it's plot driven, suspenseful and shocking in its characterization. And again its major failing is that the resolution is too easy—a failing Collins would fix in the future, as he learns to pace his suspense.

His many stories, novels and plays, in which he developed his lively style through the 1850s, were popular with the reading public—which other British writers noted.

But it's The Woman in White that is considered his first masterpiece. From an encounter with a ghostly figure on a moonlit road, the novel develops organically, deepening and widening the story as told from multiple viewpoints. The story is not supernatural but an engrossing melodrama with enchanting characters, crisp dialogue and a multi-layered plot. And it also manages to advocate for the rights of married women.

The followup, No Name, is similarly provocative, this time on behalf of children born out of wedlock. Suspense and melodrama are again at the fore, centering on the heart-breaking case of two brutally treated orphans. But ironically the villains of the piece emerge as the most engaging characters. Collins has a habit of presenting his antagonists as full-fledged human beings, rather than as stick opponents. Denounced as immoral in its time, No Name was popular with readers and has come to be recognized as a minor classic.

In his next novel, Collins was thought to have this time gone too far. Armadale carries all the authors' developing trademarks. His longest tale to date features a convoluted plot of romance, subterfuge, and criminality—not to mention its fill of apparitions, mistaken identities, fateful coincidences, sexual intrigue, violence, fraud and scandal.

Most scandalous at the time though was that Collins gave over a large chunk of the narration to the letters and diary of the novel's female villain. Today's readers may find those sections the most engaging. The evil-doing character comes alive as none of the good people do—in some ways becoming the most sympathetic character, without us ever losing sight of her terrible deeds.

Collins recovered in the eyes of readers and critics with The Moonstone (1868), another acknowledged masterpiece. Here he cut back his effects to focus on the central mystery of a stolen gem, which led to The Moonstone being called the first mystery novel. (It isn't.) It still, however, features several of Collins's trademarks, such as multiple narration and so-called scandalous elements—in this case, a depiction of drug addiction.

Collins was personally acquainted with drugs. The gradual fall-off in the popularity of his works after The Moonstone is often attributed to a laudanum addiction. Still, his next novel, Man and Wife (1870), which returned to women's rights in marriage, more pointedly this time, was a popular success and remains well regarded.

As late as 1881 with publication of the seminal detective story "Who Killed Zebedee?" and the anti-religious (some say, anti-Catholic) novel The Black Robe, he was producing significant works.

These later novels are rather obscure today though, which is a pity. If you find one, give it a try. It can't be guaranteed to be an entirely great piece of writing but there's bound to be something of interest in it.

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes