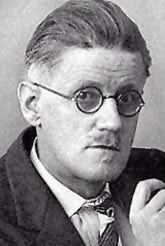

James Joyce

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

Born

1882

Died

1941

Publications

Novels, stories, poems, play

Writing language

English

Literature

• Dubliners (1914)

• A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

• Ulysses (1922)

• Finnegans Wake (1939)

Novels

• A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

• Ulysses (1922)

• Finnegans Wake (1939)

Stories

• "Araby" (1914)

• "Two Gallants" (1914)

• "The Dead" (1914)

Story Collections

• Dubliners (1914)

Irish Literature

• Dubliners (1914)

• A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

• Exiles (1918)

• Ulysses (1922)

• Finnegans Wake (1939)

On books, writers and writing

1922

The pity is that the public will demand and find a moral in my book—or worse they may take it in some serious way, and on the honour of a gentleman, there is not one single serious word in it....

All great talkers have spoken in the language of Sterne, Swift or the Restoration. Even Oscar Wilde. He studied the Restoration through a microscope in the morning and repeated it through a telescope in the evening. [In Ulysses] they are all there, the great talkers, them and the things they forgot. In Ulysses I have recorded, simultaneously, what a man says, sees, thinks, and what such seeing, thinking, saying does, to what you Freudians call the subconscious—but as for psychoanalysis, it's neither more nor less than blackmail.

Interview in Vanity Fair

1922–early 1930s

The purpose of [Henrik Ibsen's] The Doll's House...was the emancipation of women, which has caused the greatest revolution of our time in the most important relationship there is—that between men and women; the revolt of women against the idea that they are mere instruments for men.... The relationship between the two sexes is now on a different basis, but I do not know if they are happier or unhappier than they were before; I suppose it depends on the individuals. But I do know that Ibsen has been the greatest influence on the present generation; in fact you can say that he formed it to a great extent. His ideas have become part of our lives even though we may not be aware of it....

[Thomas Hardy is] something of a poseur [in Tess of the D'Urbervilles] ...with his big butter-up of a dairymaid; the wicked squire with his curled moustaches and his dog-cart; her easy rape, and the sequence of the illegitimate baby; and then the biblical Angel Clare; their contrived misunderstandings, and that final drama of the murder; and Angel and Tess's sister standing outside the jail to see the black flag go up. To me the whole story is reminiscent of The Murder in the Red Barn or The Woman Pays. Also some of the writing is as clumsy as the plot.... If you analyze his plots you will see that they contain all the tricks and subterfuges of melodrama, that ancient and creaking paraphernalia of undelivered messages, misunderstandings and eavesdroppings, in which the simple are over-simple, and the wicked are devilish....

Turgeniev was a sentimentalist who wished to remain enamoured of his own sensualism. He saw life in an ordered fashion, in spite of his proclaimed admiration for revolutionaries; in fact, he seems to have taken a special pleasure in taming and defeating them, as he tames and defeats Bazarov in Fathers and Sons and, in contrast to Dostoevski, for example, he was a nicely mannered Russian gentleman playing occasionally with fire but taking care never to get burnt. Tolstoy was a more sincere man in my opinion, for Turgeniev preferred his slippered ease and his literary circles to anything else, and the only people who are convincing in his novels are his anaemic gentlefolk. His interest was in isolation and not in action, and his world is a faded world of watercolours. I admit he was an admirable person, and you cannot help liking him as you like a weak but pleasant personality, but I cannot admire him as a great writer. I think his best work was those early Sportsman's Sketches of his, for in those he went into life more deeply than in his novels, and reading them I get the impression of the confused and simmering cauldron that Russia was in the 1840s, before the great boil-over.

[Chekhov] brought something new into literature, a sense of drama in opposition to the classical idea which was for a play to have a definite beginning, a definite middle, a definite end, and for the author to work up to a climax in the second act and resolve in the last. But in a Chekhov play there is no beginning, no middle, and no end, nor does he work up to a climax; his plays are a continuous action in which life flows onto the stage and flows off again, and in which nothing is resolved, for with all his characters we feel that they have lived before they came onto the stage and will go on living just as dramatically after they have left it. His drama is not so much a drama of individuals as it is the drama of life and that is his essence, in contrast, say, to Shakespeare whose drama is of conflicting passions and ambitions. And whereas in other plays the contact between personalities is close to the point of violence, Chekhov's characters are never able to make any contacts. Each lives within his own world, and even in love they are unable to become part of the others' lives and their loneliness frightens them. Other plays you feel are contrived and stagy; abnormal people do abnormal things; but with Chekhov it is all muffled and subdued as it is in life, with innumerable currents and cross—currents flowing in and out, confusing the sharp outlines, those sharp outlines so loved by other dramatists. He is the first dramatist who relegated the external to its proper significance: and yet with the most casual touch he can reveal tragedy, comedy, character and passion. As the play ends, for a moment you think that his characters have awakened from their illusions, but as the curtain comes down you realize that they will soon be building new ones to forget the old....

Compare for instance Thackeray's social scenes in Vanity Fair with Stendhal's, how flat they are, yet they were written about the same period and deal with much the same kind of people. Stendhal never became sentimental and soft the way Thackeray did, especially over women...but Thackeray has something which Stendhal did not have: humour.

Conversations with James Joyce, by Arthur Power, 1974

1936

[Ibsen] towers head and shoulders above everyone else, even Shakespeare. Ibsen will not become dated; he will renew himself for every generation because his problems always will be seen from a new side as time goes on. He has been called a feminist in Hedda Gabler, but he is no more a feminist than I am an archbishop. He is the greatest dramatist I know. No one can construct a piece as he can. There is not an extraneous word in his work.... I am sorry I have never seen Little Eyolf. The first act is pure wonder.

Portraits of the Artist in Exile, ed. Willard Potts, 1979.

Critique • Works • Views and quotes