The Earthsea Cycle

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

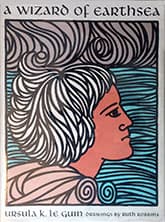

First edition

First edition• A Wizard of Earthsea, 1968

• The Tombs of Atuan, 1971

• The Farthest Shore, 1972

• Tehanu, 1990

• The Other Wind, 2001

First publication

1968 (A Wizard of Earthsea)

Literature form

Novels

Genres

Fantasy fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Five novels; A Wizard of Earthsea: approx. 66,000 words

• Novels (for A Wizard of Earthsea)

• Fantasy Fiction (for A Wizard of Earthsea)

Old story enthralls again

The story of the sorcerer's apprentice is retold many times in mythology and fantasy. It goes like this: a seemingly ordinary young lad discovers he has an odd paranormal ability, becomes a novice wizard or magician learning his art from an older mentor, faces tests along the way and eventually—often upon the death of the teacher—confronts the greatest challenge to his youthful powers, usually in the figure of an ultimate evil which only he can stop.

Variations on this simple plot are found in Ursula Le Guin's A Wizard of Earthsea, the Star Wars movies, Lord of the Rings, the Harry Potter books, and in hundreds of other fantastic tales. Even the Bible's New Testament could be read this way. (A terrific take-off on the standard story, by the way, is found in Robert Asprin's Myth series, starting with Another Fine Myth, which quickly veers off from this well-beaten path into bizarre and hilarious new territory.)

What makes a great apprentice tale then is not the overall plot structure, since this more or less follows a pattern. Rather what makes it outstanding is some aspect of how the story is told. The Harry Potter novels, for example, follow otherwise normal central characters, whom children can identify with, in their interactions with lovably (or scarily) eccentric characters. Lord of the Rings creates a multi-layered, all-encompassing world into which readers can escape.

What makes the first novel in the Earthsea cycle, A Wizard of Earthsea, stand out is its suggested depth, the impression it gives that we, along with the young protagonist, are acquiring wisdom. Not movie-style wisdom, as represented by some trinket like a ring or chalice, or not some set lesson like "be yourself" or "use the Force". But it offers a hint that through the fantasy tale we are seeing behind the trappings of our real world into some greater reality.

Le Guin is a kind of genius at telling a story simply while packing in layers of meaning. With short, matter-of-fact sentences she spins the Wizard of Earthsea plot.

The unsuspecting lad with a fateful future is Duny, also nicknamed Sparrowhawk for his rapport with birds, who lives on the island of Gont in a world of sea-splashed islands. His nascent powers are discovered when he unexpectedly saves his village from an invading army. He is then apprenticed to the great magician Ogion who reveals Duny's "true name" of Ged. But he is too powerful for Ogion's instruction and is sent to wizard school on Roke island.

Highlighting another common element in this kind of fiction though, Ged can't resist flirting with dark powers. In a fit of showing off to his schoolmates he summons a spirit which may be considered his own dark side, an evil shadow-beast that is let loose in the world. Ged's pursuit of this spirit takes him across the world to many islands, fighting dragons, evil spells and the people the evil spirit has possessed, leading to a final epic battle on the sea in a small, leaky boat.

Psychological quest

The above summary doesn't give away much. Everything Le Guin writes has to do with the environment, the interaction of the character's mind with his surroundings, and Wizard is no exception.

Is Ged really fighting an external force, or just part of himself? We're never quite sure. The quest is psychological and moral as much as physical.

I am not sure at the end though that we really have learned anything of significance. The novel certainly implies great revelations about the human condition and psyche are being made. But you may need to have a mystical bent to begin with for this to seem profound.

Interestingly though, the first of several sequels (in what became known as The Earthsea Cycle) puts this in a more down-to-earth context. In The Tombs of Atuan, we are introduced to a female counterpart of Ged, a young woman who has been trained since childhood as a priestess in a dying cult that supports an Earthsea king.

However, her mystical powers are dubious and when she meets Ged she discovers his powers too are mainly those of creating illusions. An earthly description of evil as a natural force to be overcome by human nature is also hinted.

Perhaps, it's best to take Earthsea, like all works of fantasy, as metaphorically introspective into our inner contradictions.

Which is to say, with a grain of salt. Making it all the tastier.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies