Villette

Critique • Quotes

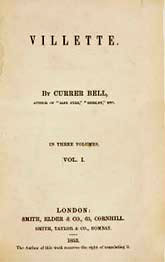

First edition title page

First edition title pageFirst publication

1853

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Literary, Gothic romance, adventure

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 210,000 words

Why don't more people love this novel?

For a few, Villette is Charlotte Brontë's big book—not just the longest of her four novels, but the most realistic, most interesting and most progressive. I fully understand this. There are times reading Villette I have to turn back to the title page to confirm that, yes, this really was written in the middle of the nineteenth century.

It takes a while for this feeling to develop while reading Villette though. At first, it is clear only that it is written much more carefully, intelligently and, some would say, boringly, than Brontë's other great work, Jane Eyre. It's almost as if the author is trying to distance herself from those earlier flamboyant, exciting works of hers and her sisters.

We seem to be launched on yet another Brontë story of a worthy young woman trying to make her way in the world through servitude and in search of a powerful, possibly wicked, man to take her under wing. Lucy Snowe appears without guile and passively accepts everything life and other people throw at her. But the ingenue eventually turns out to have a mind of her own—several minds actually—and the plot runs off in unexpected directions.

The misleading narrator

Its central character is a woman of greater complexity than ever seen previously, revealing inner battles between self-delusion and revelation that bely her plain appearance and her plain name. But she also uncovers greater convention-defying strength—hidden depths beneath the smooth surface to live up to her surname.

We also learn not to trust her. Lucy Snowe may be the original unreliable narrator. Or not just unreliable, but purposely misleading—at times quite annoyingly so.

And what are we make of the great long hallucinogenic passages exploring Lucy's psychology that are prompted by what seem to be drugs or mental breakdown, or, most likely, both? These are the sections that seem to be precursors of the stream of consciousness of Virginia Woolf (an admirer of Villette) and James Joyce, or even the trippy experiments of certain 1960s and 1970s authors. Not quite though, for these passages are too abstract and intellectual, as if pre-Freudian entities are fighting it out in Lucy's mind. But startlingly innovative nonetheless.

And then we come to Villette's inconclusive ending, again heralding twentieth-century writing. It is famously considered ambiguous, though I think it is quite clear what happened both narratively and emotionally. Despite being perplexing at first—because unexpected—it resonates afterwards because it is realistic, unlike the easy victory at the end of Jane Eyre. It doesn't conclude Lucy's life—and why should a novel be required to do that for a female character?—but it does conclude a chapter in her life satisfactorily. She can move on, knowing who she is and her true powers.

Or maybe that's just the positive interpretation I impose on the final puzzle of Villette. After all, the narrator is explicit in saying she's letting us imagine the ending.

Untangling contradictions

So do these modernistic, or post-modernistic, features explain why Villette is generally considered less accessible—more difficult—than the ever-popular Jane Eyre? Partly.

Lucy Snowe is not a plucky character you can warm to quickly as you can to Jane Eyre, though she does grow on you as you untangle her contradictions—albeit never entirely. But that makes it real, doesn't it?

Perhaps more tellingly, no man in Villette comes up to the commanding standard of Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre (or Heathcliff in sister Emily's Wuthering Heights, for that matter).

One of the two men who interest Lucy is handsome but proves weak in character and superficial with women. The other is, frankly, unattractive, dogmatic and chauvinist. (Okay, all male characters were chauvinist back then, but this one is particularly repulsively so.) Lucy eventually wins one of them over without ever scaling the blindingly romantic heights expected in such a novel. And the purported denouement of that relationship falls far short of an operatically tragic conclusion.

All to the credit of the author's honesty. But not necessarily gaining the novel the legions of fans it should have.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes