Under Fire

Critique • Quotes

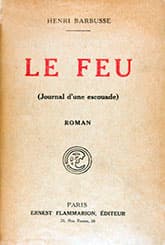

First edition title page

First edition title pageSubtitle

The Story of a Squad

Original title

Le Feu: journal d'une escouade

First publication

1916

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Literary

Writing language

French

Author's country

France

Length

Approx. 120,000 words

The chaotic poetry of war in a novel

I really wanted to love this book. It's one of the sharpest indictments of war ever written in fictional form, a groundbreaking work by a sincere, progressive author.

But I found I cannot love it as a whole. I can only like it, appreciate it, recognize its significance. And love parts of it.

When discussing Henri Barbusse's Under Fire, it's almost impossible not to compare it to Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front. Not just because they are the two most moving novels to come out of the Great War, but because they were written by and about men who fought in opposing armies. Together they show how similar the experiences were on both sides of that devastating, inter-imperialist conflict. So achingly, humanly—inhumanly—similar.

But if All Quiet is much better as a novel, Under Fire is the more chaotic, if poetic, rendition of the horrors of war.

Much of Barbusse's novel, subtitled The Story of a Squad, is episodic. Disconnected scenes portray the surreal experience of the men in the trenches, from the most petty incidents to matters of life and death. It does have its effect. We get to know the men in the scattered way we get to know people in real life. The staccato, horrific events of war defy the soldiers, and the reader, to maintain equilibrium, or sanity. Or memory. The soldiers complain they'll never be able to remember what they are going through to tell others afterwards. It is this task of telling others—telling it like it is, as a much later generation will put it during a much later war—that Barbusse takes up.

Unnerving contrasts

At times while reading however, I wished Barbusse would write less choppily and tell more complete stories. One can only take so much fragmented unreality before it starts to seem, well, unreal. One begins to resent so much detail being piled on and to yearn for more humanity.

The most effective chapters of Under Fire may be those that take place when the battles stop and the soldiers wander through disappeared towns or mingle with uncomprehending civilians—before another hellish slaughter begins. The contrasts are deeply unnerving. (Another similarity to All Quiet on the Western Front.)

The pacifist poet Siegfried Sassoon apparently read Under Fire when he was fighting in the same war and declared it the first book he had ever read to bring the experience of war home to civilians. This inspired him to produce his own famous literature on the war. (An account of Sassoon's experience in the war is part of Pat Barker's Regeneration novels many years later.) The best parts of Under Fire still have that stirring effect today.

A word about the English translation. I've read only one, the original, I think, by W. Fitzwater Wray. It's terrible. I don't know how well the French is interpreted but the translator has no grasp of the English idiom. Clumsy constructions mar every page. If you find another translation, go for it.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes