'Tis Pity She's a Whore

Critique • Quotes

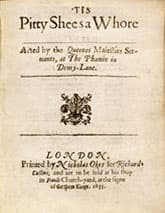

First edition title page

First edition title pageAlso known as

'Tis Pity; Giovanni and Annabella; The Brother and Sister

First performed

c.1626–1633

First publication

1633

Literary form

Play

Genres

Tragedy

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Five acts, approx. 2,400 lines, 17,000 words

Pity us all

Perhaps the most shocking thing about 'Tis Pity She's a Whore is that it still shocks.

John Ford's plays were written in a period of increasingly scandalous theatre. After Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, English drama took a more shocking and grisly turn that critics have termed "sensationalist". (I would argue its content was really no more provocative than that in works of the earlier hallowed playwrights, just presented more explicitly. But that's a discussion for another time.)

The first surprise of 'Tis Pity She's a Whore for a modern reader is that it has nothing to do with prostitution. "Whore" is used in the slanderous sense of a woman being called loose, like a "slut" in more recent vernacular. In fact, the titular declaration is not even delivered until the last line in the play, and this by a religious figure who is not himself portrayed as being particularly virtuous.

The real scandalous subject matter of 'Tis Pity is incest. What is most disturbing about it is how Ford manipulates our attitude toward it in the persons of his incestuous young characters Giovanni and Annabella.

Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet had enlisted our sympathies on the side of the young lovers, against the social strictures that would keep members of feuding noble families apart. Love conquers all, breaches all barriers, though society's condemnation dooms the lovers. In the end, we all—the surviving characters and the audience—learned lessons in love and tolerance from the tragedy.

Now imagine upping the ante of that great romantic and tragic play, raising higher the social bar to the point that most right-thinking folks would be repulsed by the love affair. I'm convinced this is what Ford, who would have been very familiar with the Romeo and Juliet story, had in mind. So in a similar Italian aristocratic setting, he joins a young man and young woman in a loving, lusty relationship, but this time they're siblings. They're even abetted by similar secondary characters, a friar confidant for Giovanni (as for Romeo) and a tutoress confidante for Annabella (like Juliet's nurse). Plus we have the similar complicating subplot of various nobles, unaware of the illicit attachment, vying for the young lady's hand in marriage.

A turn into darkness

Giovanni's love for his sister is revealed in the play's first scene with the friar, who tries to dissuade him. The lad hasn't told his feelings to Annabella yet. And here is Ford's first great and unsettling accomplishment: we immediately fall into sympathy with the young man.

He's obviously in love. It seems like a quite standard dramatic scene, the besotted youth nervous about approaching the object of his ardour. He's unwilling—in Shakespearean terms—to admit any impediment to love. To all his advisor's objections to the relationship he comes up with sophistical rationalizations. And we tend to accept them. For he's young, idealistic and madly in love. He doesn't seem abusive or twisted in some way we might associate with a familial predators.

When he does open his heart to his sister, we hope with him for a happy reception. Despite whatever sentiments about incest we might bring to the story, we are easily seduced into accepting it. It's the same kind of warm and fuzzy feeling we might get from the early exchanges of Shakespeare's star-crossed lovers.

Ford's blank verse (the iambic pentameter favoured by both the earlier Elizabethans and his contemporaries), creating the poetry we expect in love stories of the time—though not as elaborate or effusive as Shakespeare's verse. Still, in starker times, he sets up the relationship as we've come to expect of more conventional love affairs.

From that point, however, the story turns dark indeed. Hellfire is threatened, a lover is betrayed by marriage, an awkward pregnancy is revealed, people are stabbed, others poisoned, eyes are gouged out, burning at the stake is ordered, vengeance runs rife, a massacre ensues. And the most shocking mental image of all lingers: a ripped-out human heart being brandished on a dagger.

Sparking outrage

Sensational stuff indeed.

Yet, what critics and spectators seem to have found most upsetting is Ford's attitude toward it. People have argued for a long time over whether in the play he is condemning the incestuous relationship, showing the disastrous consequences of such sin, or he is sympathetic to the lovers and satirizing society's over-reaction to their affair, resulting in death and destruction all around.

A less hysterical consensus is that the playwright is neither supporting nor condemning but just showing what is. People can't help falling in love in ways that offend others, and others can't help but take drastic measures against what offends them direly. Fate, which is mentioned quite often in 'Tis Pity, cannot be denied. This applies not just to the incestuous love affair but to the over-the-top emotional, violent and possessive responses of all the characters.

And, of course, this interpretation of Ford's views—or lack of views, his seeming amorality—is also a source of outrage at the play. He should condemn (or sympathize with) incest. The madness that seems to afflict all when their expectations are thwarted should be explained. Even a reader nearly four centuries later can still feel unsettled at the lack of moral resolution—if this is indeed Ford's intent. What exactly is the lesson for us here? Nothing apparently. It's just the way things are, the way we are.

For Shakespeare and others of his time, character is fate. There are hints of this in 'Tis Pity She's a Whore, hints that Giovanni's arrogance helps bring disaster down upon his love and life, and that others are too weak or ignorant to resist the temptation to lash out for revenge.

But for the most part in Ford's play, the fault is in our stars—which is to say in our nature. The human condition as a whole is pitiable.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes