The Country Wife

Critique • Quotes

1934 edition

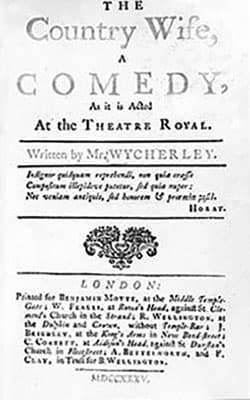

1934 editionFirst publication

1675

Literature form

Play

Genres

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Five acts, approx. 30,000 spoken words

What's love got to do with it?

Your first go at The Country Wife may leave you mystified. Especially mixed up over all the criss-crossing plots involving characters who can scarcely be told apart. They're all randy, witticism-spouting, wealthy layabouts conspiring to get into each others' pants.

This may be part of William Wycherley's aim. Not to confuse you, that is, but to wallow in the licentiousness of the aristocracy, which had recently returned to power in England.

In the years after dethroning royalty Cromwell's Commonwealth had imposed its Puritan ethics on the arts, shutting down the nation's theatres. With the restoration, the high-born patrons of the revived stages demanded plays focus on them. Not just bring back the Elizabethan dramas of love and power among the nobility that Shakespeare and company had produced, but present their more jaded interests. And written in conversational language, without all that verse and metre with which earlier poet-playwrights dressed up their subtle meanings.

Like other plays of its period, The Country Wife is all about sex—or rather about the game of sex. Sure, they still go on about "love" and lovemaking, but it's obvious they're talking about superficial physical attraction based on style, status, wit and wealth, not the deep, self-justifying emotional connection explored in Shakespeare's time.

As a frank exposition of meaningless sexuality, this early peak of Restoration drama was considered too wicked for popular presentation in later eras, until the play made its comeback in the mid-twentieth century, recognized for its other more enduring qualities. It reminds one of the quote from the Woody Allen film Love and Death: "Sex without love is an empty experience...but as empty experiences go it's one of the best."

But don't expect to be shocked by The Country Wife. It's not particularly explicit by today's standards in either language or action. The sexual acts, whatever they are, take place off-stage, and the on-stage banter is not so much about them as it's obsessed with the one-upmanship of competitive seduction.

Also don't expect in the first go-through to laugh out loud, despite all the wit that's said to be on display in this play. Quite a lot of the comic prattle may go over your modern head, until you've become comfortable in the characters' milieu. If you do learn to get the cynical humour though, it is quite funny.

A love story found

Critics have clashed over whether The Country Wife revels in the frivolous, libidinous lives of the blue bloods or is a satire on them. Could the play be lampooning the lords and ladies of England, the same way that Molière was making fun of the pretentious in France around this time? (Though the French playwright more often took the upwardly mobile middle classes as his targets.)

Evidence that Wycherley has mapped out a satire may be found in the anomalous subplot involving Harcourt and Alithea. Yiou can see them as acting out more of an old-fashioned love story that puts all the other self-centred schemers around them to shame.

Or does it? Some of those other schemers also succeed mightily, most notably the old reprobate Horner, whose pretense to be impotent tricks other men's wives into his clutches repeatedly—without any comeuppance for him by the end of the play. If anything, the drama seems to resist moral judgment.

You see, this play offers so many complicating factors for anyone wanting to pigeon-hole it. As mentioned before, the play is really...well, complicated. And this again is by demand. Patrons may have appreciated the entertainment value of Molière's work, but they also wanted more complex plots with lots of opportunities for jokes to be cracked and twists to be turned at nearly every characters' expense.

The Country Wife offers up no one central fool whom the fates play with, as in the classic French comedies. The closest to that would be Sparkish, a dull-witted fop who loses the woman he's engaged to through his own comical stupidity, but he's a supporting character at best.

There's actually no central plot in The Country Wife either, come to think of it. Just a lot of subplots wrapped around each other and coming to a head together.

Life without consequences

The play's title might be thought to privilege one of those plots, the attempt by Pinchwife to keep from his fellow London lechers his innocent rural wife, who turns out to be as excited by the prospect of affairs in the big city as any of the jaded sophisticates. (By the way, don't expect to find the naturally naughty wife a kind of common person that lower-class audiences—if there were any—could identify with. She's no farm girl. She's "country" in the sense of a "country home" or landed gentry.)

There are no really serious repercussions from any of the philandering. There's no moralizing. The biggest sin seems to be to have a poor sense of humour, to not be able to keep up with the wit that's flying about in all directions.

At times in the hierarchy in which the equally well-to-do characters rank themselves, it seems having a clever tongue is on a par with being sexually powerful.

But it's all in good, clean...er, dirty fun. As much as in any modern bedroom farce in film or on stage.

No one dies. No one gets a disease. No one loses economic power.

And no one suffers real heart-break, since—apart from our one pair of true lovers—no one has a real heart.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes