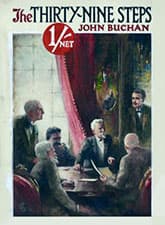

The Thirty-Nine Steps

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1915

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Crime, mystery, espionage

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 41,000 words

Conspiracy in plain sight

There is not a lot to say about the narrative structure or the characters or the writing in this famous novel. The Thirty-Nine Steps is a seminal tale of intrigue, a classic early story of an innocent man drawn into dark doings of murder and espionage, and finding himself pursued by both police and enemy agents.

John Buchan tells it well, with a minimum of fuss, nothing extraneous to the main story. The characters are quickly established, tending toward British upper-class and lower-class stereotypes and nothing between. The fast-paced plot keeps you turning the pages.

Today it reads as somewhat old-fashioned and the climax is a bit of a drag by recent standards: no last-minute twist in which it's revealed that some high-ranking British authority whom our hero trusts is in on the black plot.

But it must have be a thrill to readers of its time, imagining themselves the everyman hero, Richard Hannay, brought face to face with evil in the cloak-and-dagger world, a world they could suppose co-exists unseen with theirs, behind the headlines and the political cover-ups.

Much more would be made of this by writers to come. And it would serve as the basis for numerous films.

Another theme that has been picked up by thriller writers is the idea that evil is hiding in plain sight in our civil society. Even more so, the idea is put about that no one is who he or she seems. The villains of the piece are the prime examples of this, of course, but Hannay more than once passes himself off as someone different—a milkman, a politician and a Scottish herder—to evade both police and killers.

Charges of racism

One aspect of The Thirty-Nine Steps that does get discussed today is its alleged racism, specifically anti-Semitism. The late Canadian novelist Mordecai Richler caused a stir by pointing to the most offending passage, appearing early in Buchan's book:

"...The Jew is everywhere, but you have to go far down the backstairs to find him. Take any big Teutonic business concern. If you have dealings with it the first man you meet is Prince von und zu Something, an elegant young man who talks Eton-and-Harrow English. But he cuts no ice. If your business is big, you get behind him and find a prognathous Westphalian with a retreating brow and the manners of a hog. He is the German business man that gives your English papers the shakes. But if you're on the biggest kind of job and are bound to get to the real boss, ten to one you are brought up against a little white-faced Jew in a bath-chair with an eye like a rattlesnake. Yes, sir, he is the man who is ruling the world just now, and he has his knife into the Empire of the Tzar, because his aunt was outraged and his father flogged in some one-horse location on the Volga."

One should immediately realize this is dialogue from a character and by itself can show only that Buchan includes an anti-Semitic character in his novel—namely the journalist Scudder—not that the novelist or his novel is anti-Semitic. Though one might still wonder why.

Buchan's defenders have also pointed out that in this passage and in other lines just before this passage, the character explains that centuries of persecution of the Jews have led to this situation. But this defence is naïve. Noting historical justifications does not not balance out repeating hateful conspiracy theories.

A more effective defence is to point out Scudder's racist assessment is not adopted by the novel's narrator nor justified in the novel's development. In fact, the postulated Jewish-anarchist-capitalist plot (there's a weird combination for you) is discredited in the novel, in favour of a simpler matter of international espionage by Germany against Britain.

Moreover, one of the characters we're obviously meant to admire, Sir Walter Bullivant, refers to Scudder's "odd biases" about the Jews and says Scudder was off-track in his conspiracy theories. For some critics this comes too late in the novel and is too slender to offset the effect of the earlier, more elaborated alleged anti-Semitic speech.

Also worrying is a throwaway remark the narrator does make about halfway through:

...I was desperately hungry. When a Jew shoots himself in the City and there is an inquest, the newspapers usually report that the deceased was 'well-nourished'. I remember thinking that they would not call me well-nourished....

I really don't know why a Jew is mentioned here at all. I can think of both innocent and malevolent interpretations of this sentence. Just as with Shakespeare's depiction of Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, one can put pieces of evidence together to show the author is a raving racist or put other interpretative bits together to show he's an undiscriminating humanitarian.

In these situations, the only fair course is to consider the work as a whole, to determine whether it is hurtful toward one group of people or is meant to heal divisions among us. In the case of Shakespeare, there is no doubt The Merchant of Venice is a work of understanding, promoting mercy among humankind. With The Thirty-Nine Steps it is not so easy to say. At best it is neutral. At worst it displays unattractive prejudices prevalent at the time. I doubt anyone is going to become an anti-Semite after reading Scudder's diatribe, but it does provide some ammunition to anti-Semites willing to take support from out-of-context quotations. You can argue about whether Buchan can be held accountable for that.

Buchan was obviously a very conservative gentleman and likely as insensitive to racial stereotypes of the time as he was to the class stereotypes in his novels. Today a writer would be more careful—as soon as the keys J-E-W are pressed on his keyboard he would immediately consider any ramifications and misunderstandings that might be associated with them. And this is a good thing. Whether Buchan was innocently unaware of the impact of his characters' remarks or whether he was hinting at his own secret views, I do not know.

Buchan as a public figure was noted as an opponent of Nazism and a supporter of Jewish causes, at least in his later life, so I lean toward the more benevolent interpretation. But who knows what lay deep in his heart in 1914 when he was writing The Thirty-Nine Steps?

In any case, I do not find this novel anti-Semitic in its overall thrust. As a product of the latter-twentieth century, however, I am sufficiently concerned to be on the lookout for any additional evidence or argument either way. And that too is a good thing.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies