Nicholas Nickleby

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

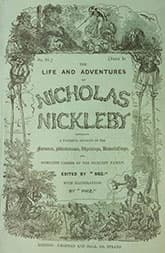

Serial publication, 1838

Serial publication, 1838Also known as

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby and The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Containing a Faithful Account of the Fortunes, Misfortunes, Uprisings, Downfallings, and Complete Career of the Nickleby Family

First publication

1838–1839 in serial publication

Publication in book form

1839

Literature form

Novel

Genre

Literary

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 323,000 words

The hero without qualities

Nicholas Nickleby is Charles Dickens still trying to work out how to sustain a novel. It's usually classified as his third novel, coming hard on the heels of the sketchy Pickwick Papers and the diversely stitched together Oliver Twist.

As in Oliver Twist, the narrative of Nicholas Nickleby presents a panoply of tragic, satiric, suspenseful and melodramatic elements featuring eccentric characters—again in episodic fashion suited to serial publication. But this time a greater effort is made to mix the elements together as integral parts of the biography of the main character. It may be significant that while the previous novel's long title was The Adventures of..., this one is The Life and Adventures of....

As others have pointed out, this is the first Dickens novel with an actual hero. Nicholas Nickleby is the righteous young man who sets about to right the wrongs that afflict his family and those who come under his care. He's continually enraged by the injustices he faces in English society of his time.

Following his exploits, most of the novel is serious narration of intrigues and confrontations, interspersed with Dickens's trademark humorous breaks to lighten the weight.

But having the main character carrying the burden of the evolving plot has a down side. There's not enough time between his "adventures" for revealing his inner life. Despite all the attention paid to his behaviour, Nicholas himself remains largely a cipher. Readers may root for him but never lose their hearts to him as they did so willingly to Oliver.

Nicholas is an unthinking hero at best. Successful in all his endeavours without having to overcome any interior qualms, as far as we can tell. He sees people ill treated and he saves them. He joins a theatrical troupe and is an immediate sensation on stage. He meets a beautiful woman and she falls in love with him before words are spoken.

At times he is given to less than noble behaviour, blinded by his own desires, treating others cavalierly and ordering them about. We accept his benevolent status mainly because other characters attribute absolute virtues to him.

Dickens appears to have purposely set up this contradiction. In a preface to the book edition, he writes:

If Nicholas be not always found to be blameless or agreeable, he is not always intended to appear so. He is a young man of an impetuous temper and of little or no experience; and I saw no reason why such a hero should be lifted out of nature.

But still, for a titular character Nicholas has remarkably little self-awareness. Privy to meagre introspection on his part, we often have no idea why he's acting as he does, except that he's outraged. This may be typical of a young man "in nature" but it prevents us from sympathizing with him as we do with other Dickens heroes.

The lively oddballs

Equally a blank is his sister Kate Nickleby. For much of the novel the two siblings are featured in alternating chapters. Kate is often cast into the position of being a passive victim of others, though she shares her brother's propensity for doing whatever's required to support her family and to balk at injustice. But again we know little of this admirable character's inner struggle.

As often in Dickens, the characters that do come to life are the oddballs—the villains, the victims and the comic relief—who can be picked out by their humorously descriptive Dickensian names: the abusive schoolmaster Wackford Squeers, the abused and sickly Smike, the jealous milliner Miss Knag, the melodramatic impresario Vincent Crummles, the penny-pinching Arthur Gride, his thieving housekeeper Peg Sliderskew, the scheming nobleman Mulberry Hawk, his dupe Lord Verisopht and his interchangeable henchmen Pluck and Pyke....

Somehow, despite the best efforts of money-grubbing uncle Ralph Nickleby and the other conspirators, everything works out just fine for Nicholas and friends, except for poor Smike, whose demise is the most heart-wrenching turn in the novel. It never seems in doubt Nicholas's side will eventually triumph and every villain will be vanquished.

In the last third of the novel Dickens seems to realize some romance is required. Several love matches are mechanically set up. At least three couples are made to fall in love, and ultimately marry, without ever passing through stages of developing relationships. And we're to understand all the hastily considered marriages turn out happily.

However, as in several other Dickens storylines, the success that caps the protagonist's efforts is helped along by two happenstances: the timely revelation of an inheritance and largesse from a benefactor. In this novel it is discovered that Madeleine Bray, the impoverished woman Nicholas falls for, is really an heiress and when they marry the wealth will pass to him.

'Mankind was my business'

His other lucky break is coming under the protection of the Cheeryble twins, rich businessmen who seem to spend all their time helping others with jobs and money. Their altruism not only aids Nicholas's family and associates materially but serves as inspiration to all they come in contact with.

You may recognize this as a Dickensian cliché—the wealthy entrepreneur who takes not profit but mankind as his business, as the ghost of Marley puts it in A Christmas Carol. The character usually appears as a contrast to the money-grubbing businessman, here represented primarily in the person of Ralph Nickleby. Dickens's generous businessmen continue to thrive socially and financially, while the selfish businessmen end their days in ruin, or in the case of Nickleby by committing suicide.

This is the reformist author's plea for capitalism with a kind face. See, by helping the poor, by contributing to the wellbeing of society at large, the rich can also provide themselves more fulfilling lives. Goodness is rewarded all around.

It's often been pointed out how naïve this is. The goodhearted Cheerybles (again, the appropriately odd name) are particularly implausible. Surely, two men so completely devoted to altruistic pursuits would never have been able to create their wealth in the first place, let alone be able to hold on to it afterwards. But Dickens must have been aware of this criticism, for he wrote in his preface that the brothers were drawn from life:

But those who take an interest in this tale, will be glad to learn that the Brothers Cheeryble live; that their liberal charity, their singleness of heart, their noble nature, and their unbounded benevolence, are no creations of the Author's brain; but are prompting every day (and oftenest by stealth) some munificent and generous deed in that town of which they are the pride and honour.

After publishing this information though, Dickens reported receiving thousands of letters from people seeking loans, gifts and investments from the businessmen the characters were based on. Their combined requests "would have exhausted the combined patronage of all the Lord Chancellors since the accession of the House of Brunswick, and would have broken the Rest of the Bank of England", he estimated and he added, "The Brothers are now dead."

Which makes one wonder whether the twosome ever really existed to the extent they appeared in Nicholas Nickleby.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies