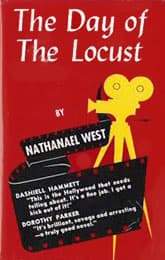

The Day of the Locust

Critique • Quotes • At the movies

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1939

Literary form

Novel

Genres

Literary, satire

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 52,500 words

Another end of days

The Day of the Locust was so underrated in 1939 when it came out and in the years immediately following author Nathanael West's death in 1940, that when critics eventually rediscovered the man's works they overcompensated for their earlier neglect by praising it to the skies.

In some quarters The Day of the Locust has been lauded it as one of the most important novels of the twentieth century.

This turnabout may also have to do with timing. West's jaundiced take on American culture was not exactly welcome in the patriotic war and postwar periods, but was better attuned to the more rebellious zeitgeist of later years.

It's a similar fate that befell The Great Gatsby (1925) by West's friend—though the Scott Fitzgerald's work that The Day of the Locust most resembles is the unfinished satire on Hollywood, The Last Tycoon.

Like Gatsby, West's novel is often said to be a critique of the "American Dream." But what that dream is supposed to be can vary widely. For some the American Dream is the rags-to-riches story in which anyone can reach the top if they work hard enough. For others it's the mythically content middle-class life in the suburbs with a spouse, two kids, two cars and all the consumer goods one can consume. For others it's the immigrant hope of finding freedom, justice and equality in the new world.

Bonfire of vanities

In The Day of the Locust the central dream is of stardom. Of fame achieved through appearing in Hollywood movies. At least that's the dream represented in the self-absorbed, aspiring actress Faye Greener, and in the masses of people who fill the streets at movie premieres seeking glimpses of the stars and in the novel's climax become a savage mob.

Other dreams crushed along the way are those of the men who aspire to Faye's affection and/or bed. The main character, artist Tod Hackett, decorates movie sets while trying to create a masterpiece of grotesque modern art he calls "The Burning of Los Angeles". Nervous accountant Homer Simpson (not to be confused with you-know-who) comes from the Midwest to California for his health and peace of mind but, strung along by Faye and picked on by everyone else, turns into a homicidal wreck.

They're surrounded by other hustlers, failed entertainers and figures reduced to prostitution, pornography and attempted rape.

And, it almost goes without saying, the insider's look at Hollywood (West, like Fitzgerald, was a studio screenwriter to make ends meet) shows the world of movie-making to be a cynical sham.

The collapse of all the dreams culminates in that riot, portrayed in the novel as an end-of-days event. And it is a masterful scene, the novel's climax of horror, merging in Tod's mind with his developing artwork, bringing all the characters and their dreams into the bonfire of the city.

Big bad joke

Of course, Los Angeles did not really burn. Hollywood and fan mania have endured. Wannabes still flock to California with stars in their eyes. Millions still fawn over movie stars and imagine themselves in the heroic and romantic roles portrayed on the screen. This has never ended. And the falseness and moral depravity behind the glamour of Tinseltown have become clichés in books and even in movies themselves.

But West was not necessarily predicting it would end in a cataclysm. In the novel Hackett's last, ambivalent response after having barely escaped the riot is to laugh and imitate the police siren, like it had all been a big bad joke in a book full of black humour. Hackett was playing while Los Angeles burned. As if he were—you decide—enjoying it, mocking it or accepting it as part of the ongoing American Nightmare with the implication that it wouldn't be for the last time.

Those who consider The Day of the Locust one of our greatest novels must think West is reaching down into something dark in the soul. But he deals with a very specific to a time and place. The characters are all rather superficial personalities in that milieu and when their deeper selves are exposed it's for such obvious frailties as greed, lust, jealousy and narcissism, hinting at scarcely any inner conflicts.

Even the purported protagonist Hackett (of the appropriate name), through whose eyes we mostly view the wicked world of Hollywood, harbours rape fantasies, urges he would carry out if given the opportunity. This is revealed along the way without any indication that it may be an issue to be struggled with. It's just the way people—or these people anyway—are. All we can do about it in the end is laugh and sound the alarm.

A brilliantly written novel and harrowing read that you may find more disturbing than enlightening.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes • At the movies