The Castle of Otranto

Critique • Quotes

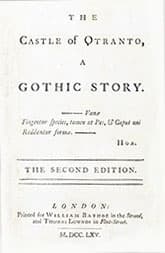

Second edition title page, 1765

Second edition title page, 1765Subtitle

A Gothic Story, added in second edition

First publication

1764

Literature form

Novella

Genres

Gothic, horror, fantasy, romance

Writing language

English

Author's country

England

Length

Approx. 31,000 words

The horrible influence

Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto is one of those "classic" works that is better known for its impact in its time that for its subsequent readability. It's more influential than admired.

In fact, any reader today is likely to find it laughable. And it's not supposed to be a comedy. Its supernatural and bloody story is meant to be delectably horrifying. As indeed many readers in the latter 1700s and the 1800s found it.

Writers after Walpole took the story's elements further, developing the entire field of Gothic horror. Chief among them were Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries of Udolpho), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein), Matthew Lewis (The Monk), Edgar Allen Poe (Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque) and Bram Stoker (Dracula).

Other writers have developed the tropes of The Castle of Otranto into the Gothic romance field, practitioners including such respected authors as Emily and Charlotte Brontë (Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre), Daphne du Maurier (Rebecca), Oscar Wilde (The Picture of Dorian Grey), Wilkie Collins (The Woman in White) and even Charles Dickens (Great Expectations).

And then there are the realist writers who took on The Castle of Otranto for parody and satire. The most prominent is Jane Austen, whose heroine in Northanger Abbey is so wrapped up in Walpole's novella and other sensational works she imbibed during her youth that she over-dramatizes the events and people in her own real life.

Like I said, influential. Although today this may be hard for the first-time Walpole readers to understand. In just the first two pages, they're likely to find themselves cringing and wondering whether the book is a self-parody.

Falling body parts

Within a few long paragraphs is quickly sketched the situation of the lord of the castle, his sickly son about to be married to a princess, his neglected daughter, his amiable wife who is unable to provide another son and the curse that they will lose the castle "whenever the real owner should be grown too large to inhabit it"—followed immediately by a gigantic helmet falling seemingly from out of nowhere to crush the son to death.

The barely credible events are off and running. More armour and body parts show up. Apparitions appear. Intrigues are launched against virginal heroines and dispossessed nobility. Victims take flight through candle-lit secret passages and underground tunnels. And everyone operates at a peek of emotion. Fear, terror, anger, passion, dread and despair drive the melodramatic plot through its turns on every page toward the final twists. (One of those involves a seeming commoner who turns out to the rightful heir to great wealth! Another melodramatic element that's been adopted by countless authors and screenwriters ever since.)

It is as ridiculous as it sounds. Or it would be if you took a moment to think about it. But Walpole doesn't give you that time, piling on one shock after another, and despite your best intentions you're likely to find yourself turning the pages as quickly as you can to find out what outrage happens next. Kind of fun if you don't take it too seriously.

When I say long paragraphs, I'm referring to editions that follow the author's original style of jamming multiple actions and dialogue from different characters into pages-long, unindented passages. This can be a pain to read, though you may find easier-to-follow editions that break up these paragraphs and mark off dialogue with quotations marks.

By the way, most references to The Castle of Otranto call it a novel, though it's listed here as a novella because its thirty thousand words or so are far fewer than the usual minimum novel length of about forty thousand. Others could argue it makes more sense to place the work in the most prestigious and larger category since the term "novella" was not even in use yet in Walpole's time.

And we wouldn't contradict anyone who would argue The Castle of Otranto crams a normal novel's worth of feeling and narrative into its relatively few pages.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes