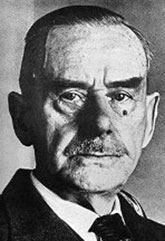

Thomas Mann

Critique • Works

Born

1885

Died

1955

Publications

Novels, stories, journalism, essays

Writing languages

German

Literature

• Buddenbrooks (1901)

• Death in Venice (1912)

• The Magic Mountain (1924)

Novels

• Buddenbrooks (1901)

• The Magic Mountain (1924)

Novellas

• Death in Venice (1912)

Stories

• The Clown (1897)

German Literature

• Buddenbrooks (1901)

• Death in Venice (1912)

• The Magic Mountain (1924)

• Joseph and His Brothers (1933–1943)

• Doctor Faustus (1947)

• The Black Swan (1954)

The politics of an apolitical writer

Thomas Mann is one of the great writers of the first half of the twentieth century, about whom it is difficult to say whether he was a herald of a new modern literary age or one of the last of a dying age.

Perhaps this is why reading him can make one feel both hopeful and slightly disappointed. His work comes across as obviously Great Literature, but somehow just never as earth-shaking as hoped.

His first great work and still his most highly regarded, Buddenbrooks (1901), has been called a very old-fashioned novel—following the fortunes of a prominent family over several generations, like many a great English, French or Russian novel of the 1800s. It is an exhaustively realistic novel in the tradition of Dickens, Balzac and Tolstoy.

At the same time Buddenbrooks has been admired for its clear-eyed, quietly ironic detachment from its subjects, and has been cited as a model for many a great family history to come in the 1900s. John Galsworthy's Forsyte Saga comes to mind, along with countless trashier novels of multi-generational conflict right up into the current era. No wonder Buddenbrooks has repeatedly been adapted for films.

Politically also, Mann has had a few turning points. Born to a wealthy family in L—beck, Germany, where his father served two terms as the equivalent of mayor, young Thomas was conservative and patriotic. Right into the First World War the author supported the German establishment with Kaiser Wilhelm at the head. His writing of this period, mainly short stories and essays, tended to extol public duty and self-sacrifice for the greater cause—namely, respectability and social stability.

This led to a split with his elder brother, Heinrich Mann, who was equally famous in the early years of the century as a German writer with radical left-wing leanings. (Among Heinrich's works is the acclaimed Professor Unrat in 1905, filmed by Josef von Sternberg as The Blue Angel with Marlene Dietrich in 1930.) Thomas argued the artist could reach spiritual fulfillment only by keeping independent of politics and focusing on the nourishment of his own ego. He reacted to Heinrich's attack on authoritarianism with a spirited defence of the establishment and claims for German superiority that bordered on racism—views he would later recant.

The publication of Mann's diaries after his death have led to the suggestion that his excessive conservatism in his early adult life was a cover for homosexual desires. Desperately wanting to fit into the establishment, he is supposed to have suppressed any indication of aberrant behaviour, according to this analysis.

Around this time Thomas Mann wrote the work that may be best known to the general public, Death in Venice (1912), concerning a middle-aged scholarly writer who falls in love—from a distance—with an adolescent boy. In the novella, the intellectual's psychological surrender to desire leads to his destruction. This work too has been filmed several times for cinema and television.

Spokesperson for humanism

However, by the end of the First World War, Mann's thoughts were shifting from his high-purposed intellectual notions toward more down-to-earth progressive and political ideas. In the post-War period he became a spokesperson for democracy and humanism in the new Germany. His novel The Magic Mountain (1924) portrays a fight with the forces of enlightenment and rationality on one side and reaction and irrationality on the other, presaging the clash with fascism that was soon to engulf Europe.

His next major work, the tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers (1933-43), retells the Bible story as a conflict between freedom and tyranny. By this time, Mann had rejoined his brother philosophically as a proponent of socialism. He has been claimed by the left as a great author ever since—although his subject matter remained high-brow and he was never a writer of proletarian issues.

When Hitler came to power, Mann with and his wife and children were forced to leave Germany. They lived first in Switzerland and then, for about fourteen years, in the United States. However, the American persecution of leftists after the Second World War disillusioned Mann and in 1952 he returned to Europe, to live mainly in Switzerland until his death.

Among his latter works is Doctor Faustus (1947), a novel not about the legend treated by Goethe but depicting decadent German culture between the two world wars.

The Holy Sinner (1951) is a fanciful account of the life of Pope Gregory, in a style that later, as practised by Latin American writers, might be called magic realism.

The unfinished parody The Confessions of Felix Krull was published in 1954. It was filmed as a mini-series for German television in 1982.

Taken together, Mann's works are diverse in style and ideas, although the conflict between personal freedom and social obligation is ever-present. What changes over the years is the answer he gives to resolve the conflict, sometimes opting for the primacy of the individual search for truth, other times stressing sublimation of the individual ego, and still other times expressing despair that there may not a resolution.

Which in some senses makes Thomas Mann a representative author of the twentieth century, but also a frustrating read at times.

He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1929, principally for Buddenbrooks.

— Eric

Critique • Works