Samuel Butler

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

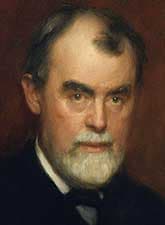

SAMUEL BUTLER portrait by Charles Gogin

SAMUEL BUTLER portrait by Charles GoginBorn

Langar, Nottinghamshire, England, 1835

Died

London, England, 1902

Nationality

English

Publications

Novels, essays, translations

Genres

Literary, satire, romance, philosophy

Writing language

English

Literature

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

Novels

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

British Literature

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

Philosophical Fiction

• Erewhon (1872)

On books, writers and writing

1872

I may perhaps be allowed to say a word or two here in reference to [Edward Bulwer-Lytton's] The Coming Race, to the success of which book Erewhon has been very generally set down as due. This is a mistake, though a perfectly natural one. The fact is that Erewhon was finished, with the exception of the last twenty pages and a sentence or two inserted from time to time here and there throughout the book, before the first advertisement of The Coming Race appeared. A friend having called my attention to one of the first of these advertisements, and suggesting that it probably referred to a work of similar character to my own, I took Erewhon to a well-known firm of publishers on the 1st of May 1871, and left it in their hands for consideration. I then went abroad, and on learning that the publishers alluded to declined the MS., I let it alone for six or seven months, and, being in an out-of-the-way part of Italy, never saw a single review of The Coming Race, nor a copy of the work. On my return, I purposely avoided looking into it until I had sent back my last revises to the printer. Then I had much pleasure in reading it, but was indeed surprised at the many little points of similarity between the two books, in spite of their entire independence to one another.

Preface to Second Edition of Erewhon

Undated

The more I see of academicism the more I distrust it. If I had approached painting as I have approached bookwriting and music, that is to say by beginning at once to do what I wanted, or as near as I could to what I could find out of this, and taking pains not by way of solving academic difficulties, in order to provide against practical ones, but by waiting till a difficulty arose in practice and then tackling it, thus making the arising of each difficulty be the occasion for learning what had to be learnt about it—if I had approached painting in this way I should have been all right. As it is I have been all wrong, and it was South Kensington and Heatherley's that set me wrong. I listened to the nonsense about how I ought to study before beginning to paint, and about never painting without nature, and the result was that I learned to study but not to paint. Now I have got too much to do and am too old to do what I might easily have done, and should have done, if I had found out earlier what writing Life and Habit was the chief thing to teach me....

A friend once asked me whether I liked writing books, composing music or painting pictures best. I said I did not know. I like them all; but I never find time to paint a picture now and only do small sketches and studies. I know in which I am strongest—writing; I know in which I am weakest—painting; I am weakest where I have taken most pains and studied most.

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler

Undated

The destruction of great works of literature and art is as necessary for the continued development of either one or the other as death is for that of organic life. We fight against it as long as we can, and often stave it off successfully both for ourselves and others, but there is nothing so great—not Homer, Shakespeare, Handel, Rembrandt, Giovanni Bellini, De Hooghe, Velasquez and the goodly company of other great men for whose lives we would gladly give our own—but it has got to go sooner or later and leave no visible traces, though the invisible ones endure from everlasting to everlasting. It is idle to regret this for ourselves or others, our effort should tend towards enjoying and being enjoyed as highly and for as long time as we can, and then chancing the rest.

The Note-Books of Samuel Butler

1897

It may be urged that it is extremely improbable that any woman in any age should write such a masterpiece as The Odyssey. But so it also is that any man should do so. In all the many hundreds of years since the “Odyssey” was written, no man has been able to write another that will compare with it. It was extremely improbable that the son of a Stratford wool-stapler should write Hamlet, or that a Bedfordshire tinker should produce such a masterpiece as Pilgrim’s Progress. Phenomenal works imply a phenomenal workman, but there are phenomenal women as well as phenomenal men, and though there is much in the Iliad which no woman, however phenomenal, can be supposed at all likely to have written, there is not a line in The Odyssey which a woman might not perfectly well write, and there is much beauty which a man would be almost certain to neglect. Moreover there are many mistakes in The Odyssey which a young woman might easily make, but which a man could hardly fall into—for example, making the wind whistle over the waves at the end of Book ii., thinking that a lamb could live on two pulls a day at a ewe that was already milked (ix. 244, 245, and 308, 309), believing a ship to have a rudder at both ends (ix. 483, 540), thinking that dry and well-seasoned timber can be cut from a growing tree (v. 240), making a hawk while still on the wing tear its prey—a thing that no hawk can do (xv. 527)....

Such mistakes and self-betrayals as those above pointed out enhance rather than impair the charm of The Odyssey. Granted that The Odyssey is inferior to the Iliad in strength, robustness, and wealth of poetic imagery, I cannot think that it is inferior in its power of fascinating the reader. Indeed, if I had to sacrifice one or the other, I can hardly doubt that I should let the Iliad go rather than The Odyssey—just as if I had to sacrifice either Mont Blanc or Monte Rosa, I should sacrifice Mont Blanc, though I know it to be in many respects the grander mountain of the two.

The Authoress of the Odyssesy

1901

if my readers note a considerable difference between the literary technique of Erewhon and that of Erewhon Revisited I would remind them that, as I have just shown, Erewhon took something like ten years in writing, and even so was written with great difficulty, while Erewhon Revisited was written easily between November 1900 and the end of April 1901. There is no central idea underlying Erewhon, whereas the attempt to realize the effect of a single supposed great miracle dominates the whole of its successor. In Erewhon there was hardly any story, and little attempt to give life and individuality to the characters. I hope that in Erewhon Revisited both these defects have been in great measure avoided. Erewhon was not an organic whole, Erewhon Revisited may fairly claim to be one. Nevertheless, though in literary workmanship I do not doubt that this last-named book is an improvement on the first, I shall be agreeably surprised if I am not told that Erewhon, with all its faults, is the better reading of the two.

Preface to Revised Edition of Erewhon.