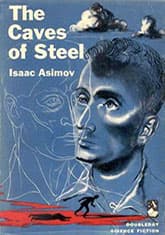

The Caves of Steel

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1954

Literature form

Novel

Genres

Science fiction

Writing language

English

Author's country

United States

Length

Approx. 67,000 words

Murder in the middle

You could say Isaac Asimov was always a mystery writer. His early science fiction works were often light on action as his brainy, talkative characters sought answers to practical questions. Why did that robot act contrary to its programming? Where is the foundation hidden in the galaxy? Why does civilization on a planet collapse every two thousand years?

But the young writer was warned by his mentor John W. Campbell that placing a conventional mystery in a science fiction setting wouldn't work because in the future a scientifically equipped detective could too easily solve any crime. Asimov recalls the warning in an introduction to a 1983 edition of The Caves of Steel, first published in 1954 and in print ever since—disproving Campbell's theory.

For in The Caves of Steel, Asimov's sleuths take on a baffling murder mystery, no less. The investigation involves many of the traditional elements of detective stories, such as suspects being interviewed, red herrings cropping up, an unorthodox cop running afoul of his superiors, and a final showdown of sorts with the perpetrator.

You could also call it a buddy cop story, in which two very different detectives clash while being forced to work together. It might even be the first such story—certainly the first pairing of a human with a robot detective.

That's not the only difference between Lije Bailey and R. Daneel Olivaw. Bailey (the man) is a resident of New York City, an earthling on a world of dome-enclosed cities, whose teeming residents hate robots as much as they fear open spaces. Olivaw (the machine) exists in a nearby outpost of Spacers, people who have colonized fifty other planets and appreciate robots as much as they dislike earthling.

The murder victim is a Spacer diplomat who was trying to convince the Earth cities to accept robots. He is killed in Spacetown, into which an earth-dwelling murderer could get only through an official port of entry or by crossing a wide space around the outpost, a seeming psychological impossibility.

Robots are also excluded from suspicion, since the novel is an extension of Asimov's earlier robot stories, most memorably collected in I, Robot (1950). It accepts Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics, preventing robots from being able to harm humans.

The Caves of Steel could also be read as a political allegory of the 1950s. The Spacer colonies were created by "individualists and materialists...carried to an unhealthy extreme" while Earth's crowded cities represent a society that "has built co-operation, if anything, too far," Bailey concludes near the end of the novel. He looks forward to the two extremes interacting to "form a new middle way" that is better than either. Writing at the height of McCarthyism, which he opposed, Asimov may be stating the position of left-leaning liberals at the time who saw a middle course between individualistic capitalism and collectivist communism as the best hope for the world's future.

Brain wracking

The ending of The Caves of Steel—beyond the solution of the crime—may seem a bit of a weak-kneed cop-out to some readers too, valuing mercy and political pragmatism over the strict rule of law.

Mystery readers who come to this novel from a modern police procedural background may also be disappointed by the investigation itself. There's no examination of the body or crime scene, no study of fingerprints or DNA, no extensive checking of alibis and backgrounds. The evidence, such as it is, is mostly tied up with the futuristic science fiction scenario. All the sleuthing seems to involve the detectives, especially Bailey, wracking their brains for possible explanations and checking clues that come their way by seeming happenstance—and talking everything to death.

(My favourite Asimov-style digression in the novel is the two-to-three pages the learned atheist spends on retelling the biblical tale of Jezebel, defending her from the Judaic authors, all to explain the name of Lije Bailey's wife, Jessie.)

But if you can appreciate both speculative fiction and crime fiction—and, even better, enjoy Asimov's trademark writing style—you can find the puzzle engaging, a page-turner to the end. Perhaps not a great science fiction novel nor a great mystery novel, but something in-between.

The Caves of Steel is Asimov's first novel in his robots series. It's followed by The Naked Sun (1957), which may be an even better mystery, though The Caves of Steel gets the larger credit for being the first successful attempt to combine the science fiction and mystery genres. Some years later Asimov added the third book in the series, The Robots of Dawn (1983), to round out the sleuthing adventures of Bailey and Olivaw—though the duo do appear in later novels that unite Asimov's various fictional worlds.

Asimov would also go on to write many mystery stories unrelated to his robots series—both with and without science fiction elements, including his sixty-six Black Widowers stories, which were first published mainly in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine and collected in six book volumes. But The Caves of Steel and The Naked Sun remain his most innovative and popular mysteries.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes