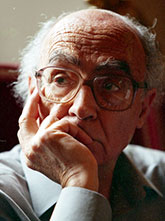

José Saramago

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

Born

Azinhaga, Santarém, Portugal, 1922

Died

Tías, Canary Islands, Spain, 2010

Publications

Novels, plays, stories, memoirs

Writing language

Portuguese

Literature

• Baltasar and Blimunda (1982)

• The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1985)

• Blindness (1995)

Novels

• Baltasar and Blimunda (1982)

• The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1985)

• Blindness (1995)

Portuguese Literature

• Baltasar and Blimunda (1982)

• The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1985)

• The Stone Raft (1986)

• The History of the Siege of Lisbon (1989)

• Blindness (1995)

• Seeing (2004)

• Cain (2009)

Literary Fiction

• Baltasar and Blimunda (1982)

At ease in the off-centre

José Saramago may be the most interesting writer of the late-twentieth century and early years of the next. And possibly the most bewildering.

He was a hardline communist whose work was hailed by such establishment critics as the late Harold Bloom who once ranked him among the world's few living geniuses. Trained as a mechanic and metalworker, he worked in the civil service and publishing industry, before eventually becoming a serious novelist in his fifties. And then, after the reaction to his anti-religious novel The Gospel According to Jesus Christ (1991), he exiled himself from his native Portugal—and became known as that country's greatest author.

But mainly what distinguishes Saramago is the odd brilliance of his prose, his ability to string together eccentrically punctuated and capitalized run-on sentences, some as long as a page, mixing majestic and awkward constructions that many writers would smooth out, and delivering it in the voice of a third-person narrator who veers between godly omniscience and peasant-level naivety and occasionally yields the floor to the thoughts and unmarked dialogue of the characters he's talking about, We don't know how but it all works, his readers may say, for the most part, It creates compelling narratives, unpretentious streams of consciousness, to engage the most non-literary of readers with writing the likes of which they have never before seen.

I have to admit, his printed text did not always have that effect upon me.

I was first exposed to his work with Blindness (1995) via an audiobook. I and another person listened to the first third or so of the novel during a long car trip. We both quickly became hooked. An intriguing and mysterious story that drew us into the characters' situation and kept us in suspense. Why had we thought Saramago was supposed to be a difficult read, a complex "literary" writer?

After the trip, I picked up a copy of the book to continue following the story. And what a shock.

That enticing narration I had listened to was now spread across the pages in a spaghetti of clauses and punctuation that I couldn't make sense of. I had to go back to the audiobook to listen as I read the text to assure myself that it was the same novel. And even then I wasn't sure I could continue with a visual reading of Blindness (a title that was becoming appropriate to me at that point).

After a while, however, I began to catch on to the rhythms of the author's prose, which had obviously been understood by the audiobook's performer. After a little time with the printed edition, I found I could read it quite naturally, as if listening in on the characters as they casually talked aloud and in their heads.

And, just as easily, I could amble through his other novels, similarly written, at my leisure.

I've never really understood Saramago's syntax enough to lay out its rules. I've seen others explain how it functions, why some but not all sentences are joined by commas and why some words are capped and how voice is passed among the characters and narrators. And maybe they've nailed it. But I cannot be bothered to keep the rules in my head as I'm reading. The prose comes naturally after awhile. For Saramago's visually unorthodox style actually captures the flow of everyday speech better than the more formally correct style. The key to it is that no key is needed—it's just punctuation that allows the rhythm of normal human speech to be expressed. It seems odd to us because we're used to punctuation that breaks up the text into chunks easily recognized by our eyes. But once I'm into a Saramago story, I'm scarcely aware of the strangeness. (With "scarcely" I'm giving myself a small allowance for those occasional times I am a little lost among his overlapping voices.)

Mainstream of consciousness

Opinion seems to be divided on whether his style helps or hurts his work. Taking the latter side, Ursula K. Le Guin referred to his "mannerisms I wouldn't endure in a lesser writer", but concluded "Saramago is worth it. More than worth it. Transcendently worth it."

But I don't think Saramago's writing is great despite his maverick style. The style is not just eccentricity on Saramago's part. Except perhaps in the original meaning of that word. His way of writing moves the story off any central axis. Every novel becomes a story of humanity at large. Swirling and still, complex and simple humanity.

It may be a form of stream-of-consciousness writing, but its subject is not the consciousness you find sliced, diced and reorganized by the famous psychological writers who introduced the approach, like James Joyce or Virginia Woolf. Not nearly so intellectual, for one thing. The psyches of his characters—whether they are kings or church officials, workers or middle-class professionals, dreamers or followers—are concerned with elemental issues of life, the issues immediately before them, such as love, work, boredom and survival. They play out their urgent needs for both social connection and independence. Through their struggles, they display a surprising lack of psychological depth, although their psychologies do run true.

The decentralized writing also serves Saramago's support for society's underdogs and a critique of the powers that be. Without dull political speechifying (for which the man was known in real life) or pedantic sermons from the literary mount. Rather, the morals of his story come through in the intermingling of his characters' and narrators' plain-spoken thoughts and motivated behaviour.

His imaginative plots often start with fanciful premises. An undiagnosed illness causes everyone to go blind and social order break down, Spain and Portugal set sail away from Europe, an eighteenth-century priest invents a flying ship powered by captured human wills. This has led some to place him among the magic realist authors like Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa. Not so much in the socialist realism camp you might expect, based on his oft-expressed beliefs.

But fantastic events in those works serve just as the groundwork for an exploration of how people react and interact under challenging circumstances. It helps to highlight the presumptions about life, death, power and relationships that we are unable to recognize in our current lives.

His unique prose also lends a mythic quality to his writing, elevating the ordinary to the extraordinary, whether he stages his story in a certain period with known historical figures in a particular location, such as among the people and rulers in the 18th-century on the Iberian peninsula in his most acclaimed work Baltasar and Blimunda (1982), or he leaves time and place, and even characters' names, largely unspecified as in the popular novels Blindness and All the Names (1997).

His obscure style and labyrinthine plots, often involving ordinary people caught up in bureaucratic phenomena, have led others to compare his work to that of modernists like Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges.

When José Saramago won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998, about half the reading world probably thought, "There they go again, selecting some obscure little writer no one's ever heard of," and the other half thought, "At last, a true giant of our time has been recognized."

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes