Samuel Butler

Critique • Works • Views and quotes

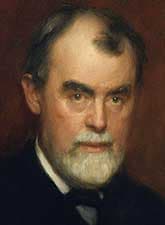

SAMUEL BUTLER portrait by Charles Gogin

SAMUEL BUTLER portrait by Charles GoginBorn

Langar, Nottinghamshire, England, 1835

Died

London, England, 1902

Nationality

English

Publications

Novels, essays, translations

Genres

Literary, satire, romance, philosophy

Writing language

English

Literature

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

Novels

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

British Literature

• Erewhon (1872)

• The Way of All Flesh (1903)

Philosophical Fiction

• Erewhon (1872)

Yesterday's genius still relevant today

Samuel Butler is one of those all-round literary guys who engage in the burning social and intellectual issues of the day and are quoted by everyone for a couple of generations, but whose fame fades with the issues of the departed day, so that only the historically minded still cite their fiery brilliance. Others in this category are G.K. Chesterton and H.L. Mencken.

Butler's ideas, however, deserve to be remembered. George Bernard Shaw wrote in a preface to his own play Major Barbara:

It drives me almost to despair of English literature when one sees so extraordinary a study of English life as Butler's posthumous "Way of All Flesh" making so little impression that when, some years later, I produce plays in which Butler's extraordinarily fresh, free and future-piercing suggestions have an obvious share, I am met with nothing but vague cacklings about Ibsen and Nietzsche.... Really the English do not deserve to have great men.

Although The Way of All Flesh (1903) has indeed become recognized as a modern classic since Shaw wrote this, Butler's name still does not trip off the public tongue as easily as Ibsen, Nietzsche, Dickens, Darwin or a dozen other lights of the late Victorian era. His writings can appear to us too wrapped in the intellectual concerns of his time. But if you do venture into his works with the intention to see past those ephemeral trappings, you find not only a lively wit but a depth and breadth that make his thinking applicable today. The questions of religion versus secularism, the organization of society, and the idea of progress are still with us today and we could still use his "fresh, free and future-piercing suggestions".

One of the impediments to Butler's popularity is that his two best-known novels, Erewhon (1972) and The Way of All Flesh, are not particularly appealing as novels. They're scarcely novels at all, more like excuses upon which to hang his remarks about the world as it is and as he would like to see it.

Erewhon is one of the more famous utopian/dystopian tales in which a traveller happens upon a strange society and spends the rest of the book observing it. The Way of All Flesh does include a more traditional and involving narrative, following the life of a young man who wrestles with the position in which his family and society have placed him, and more than half the text is devoted to the narrator, subbing as author, again observing and commenting. But such intriguing observations and comments. Both books may be hard slogs to get into initially but in each the slog is rewarded many times over.

Posthumous acclaim

Much of the story in The Way of All Flesh is taken from Butler's own life. Born in Nottinghamshire, England, he was allegedly pressured to follow in his clergyman father's footsteps into the Church. After studying at Cambridge he lived in a poor parish for a year as his character Ernest Pontifex does. Racked with doubts about his calling, he resigned and went to New Zealand in 1859 to escape his family and become a sheep farmer. While there he read about the recently proclaimed theory of evolution and wrote a satirical article, "Darwin among the machines", which would later develop into Erewhon.

His father published his letters home from New Zealand under the title First Year in Canterbury Settlement (1863) and he produced other pamphlets on religion and science.

Having made money in sheep farming, Butler returned in 1866 to England where he worked as a composer, painter and writer. His first major literary work, Erewhon, was a big success. But the follow-up, The Fair Haven (1873), attacked religion more pointedly, especially the four gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) of the New Testament, and nearly destroyed his reputation.

Upon reading Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species while in New Zealand, Butler had become a fervent evolutionist. However, his own research led him to attack Darwinism in a book, Life and Habit (1878), proposing the inheritance of behaviour. He continued on the same tack through Evolution, Old and New (1879), Unconscious Memory (1880), and Luck or Cunning as the Main Means of Organic Modification? (1887), none of which were well received.

He also produced works on Italian landscape and art (Alps and Sanctuaries and Ex Voto, 1888).

More popular were his translations of Homer from Greek into English: the Iliad in 1898 and The Odyssey in 1900. He also wrote an odd book, The Authoress of the Odyssey (1897), arguing Homer was a woman.

Near the end of his life he returned to his only big success to date with Erewhon Revisited (1901).

From about 1872 to 1884 however, Butler had worked intermittently on a manuscript for a novel based somewhat on his family and his own young adult life. Dissatisfied with it, he kept postponing its publication. He supposedly asked on his deathbed that it finally be published. In any case it was found among his possessions and The Way of All Flesh came out in 1903, the year after his death, to great acclaim. It is regarded not only as Butler's masterwork but as one of the masterpieces of English literature.

— Eric

Critique • Works • Views and quotes