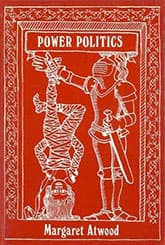

Power Politics

Critique • Quotes

First edition

First editionFirst publication

1971

Literature form

Poems

Writing language

English

Author's country

Canada

Length

45 poems

Who's got the power?

Photos of Margaret Atwood on covers of her old poetry books tend to give her a certain poetic look: intensely introspective, almost cross-eyed with sincerity, possibly crazed but intelligently so, a sixties-era Sylvia Plath hiding ferocious personal mythologies behind that sharp stare.

I don't mean to review the book cover rather than the book, but in this case the picture on the outside so well matches the work on the inside.

Now this kind of author photo is not unusual. Few volumes of poetry come with pictures of grinning writers posing with family pets, raising a beer mug or showing off the awards they've won. Serious writing is meant to be depicted as a solemn, lonely affair for geniuses who wrestle with conflicts of the soul Often it is that too.

Atwood's poetic genius, as far as she shows in Power Politics, is to translate her personal mythologies into a larger-context struggle between the sexes in a way that strkes a chord with youthful adult readers. The battle of the sexes is an ancient idea, but Atwood addresses it in light of the modern sexual revolution and the growing liberation of women. It's not the antique notion of the sexes trying to win and woo and deceive each other. Rather it's about the inequalities that still exist in emotional attachments between men and women—especially an inequality of power—despite all the social and political progress we can cite. The old imbalances persist in subtle new ways.

This way of describing it makes it sound as though Power Politics, her most popular original volume of poems, must be a political screed. It isn't. It's too personal for large political critiques. Relationships are too minutely observed and obliquely described for grand statements.

Domestic battlegrounds

Perhaps the most traditional poem is the untitled one beginning:

At first I was given centuries

to wait in caves, in leather

tents, knowing you would never come back

It progresses through historical periods in which women have waited for men to return from war, culminating with the present-day in which

...you jump up from

your chair without even touching your dinner

and I can scarcely kiss you goodbye

before you run out into the street and they shoot

This is unusual for these poems though. More often the battleground is in the motel room or the kitchen:

We are hard on each other

and call it honesty,

choosing our jagged truths

with care and aiming them across

the neutral table.

Irony, as always, is Atwood's favoured weapon, beginning with that "fish hook" poem that startlingly opens this collection (see Atwood critique). Repeatedly she uses this kind of twist to make her sharp point, often with deadly cynicism concerning love: "You held out your hand / I took your fingerprints", "I judge you as the trees do / by dying", "If I love you / is that a fact or weapon?", "Next time we commit / love, we ought to / choose in advance what to kill."

Occasionally this is both humorous and pointed:

Magnificent on your wooden horse

you point with your fringed hand;

the sun sets, and the people all

ride off in the other direction.

But often it seems viciously vengeful in a way that will appeal to all of us who have been hurt in relationships and can take vicarious pleasure in getting our own back. But I prefer the more outgoing hits at targets larger han the asshole one used to be in love with. My favourite poem (and how male this must be) is the intellectual rant about political power that begins "We hear nothing these days / from the ones in power" and ends with:

From those inside or under

words gush like toothpaste.Language, the fist

proclaims by squeezing

is for the weak only.

Given that poetry as in this book—as in this very poem—is primarily language, it presents a rather negative outlook on our relationship as writer and readers, doesn't it?

Stylistic deadend

Although I appreciate individual lines in Power Politics (see how quotable they are), I reject the overwhelming negativity, the claustrophobic feeling of us all being victims of inescapable power relationships.

Apart from the negative content, this material also seems to represent a stylistic dead end. Lines chopped up to emphasize disconnectedness, sweet images turned inside out to reveal sour linings, poems ending in punch lines.... I've seen too many miserable imitations of it from would-be Margaret Atwoods to think it leads any way forward for modern poetry.

It's interesting stuff in its way and worth reading. But I don't see how it can be built upon, either personally or artistically. It seems intended only to drive one further inside. This is not necessarily a bad thing for some people, but the kind of readers drawn to this sort of poetry are probably more in need of something to drive them out of their whiny selves.

They don't need further proofs of their powerlessness. They need empowering.

— Eric

Critique • Quotes