The Eloquent Peasant

Critique • Quotes

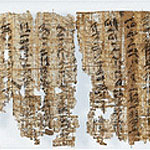

Eloquent Peasant papyrus

Eloquent Peasant papyrusAlso known as

"The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant"; "The Plea of the Eloquent Peasant"; "The Tale of the Peasant and the Workman"

First appearance

c.1875 BCE

Literature form

Story

Genres

Literary

Writing language

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Author's country

Egypt

Length

Approx. 5,000 words in English translation

Something new four thousand years ago

The three fictional works from ancient Egypt remaining in nearly full condition are all very different.

"The Shipwrecked Sailor" is an adventure. "The Tale of Sinuhe" is a patriotic epic. And "The Eloquent Peasant" is something else again—like a cross between a folk tale and the bulk of Egyptian nonfictional writing which is more meditative.

The narrative framework of "The Eloquent Peasant" has to do with a peasant who is cheated out of his possessions. The peasant takes his complaint to the chief steward, presenting his case quite beautifully. The steward reports the plea to the pharaoh who is intrigued. The pharaoh asks the steward to ignore the peasant, requiring him to keep returning and making more of these wonderful pleas. The peasant returns eight more times, each time imploring the rulers to adhere to Ma'at, an Egyptian concept variously translated as righteousness, order, justice or truth—but not just in legalistic terms, rather as features of the universe. Each time he attacks the matter in a different way, delving deeper into the implications of this abstract concept.

These parts of the story are usually translated into poetry. You may take them as precursors to the Greek dialogues, or to the moral sermons of the Bible: one passage, for instance, is rendered "Do for one who may do for you, that you may cause him thus to do", nearly two millennia before Christ is reported to have delivered the Golden Rule.

In the end, the peasant gets justice and we see Ma'at restored from the top to the bottom of society.

The story seems to work on several levels. It piques the interest of the common folks, showing someone at the lower-level of society who is able to use his golden tongue to outwit those who oppress him, while also demonstrating the wisdom of the king who recognizes the truth when he hears it.

Surprisingly interesting

At the same time, we're quite aware an ignorant peasant would be unlikely to have such a grasp of religious and philosophical principles, or of the language of such discourse. The monologues are really pitched to the educated classes, directing them to strive for the wise rule that would maintain the stability of their society and balance in the universe.

Something like that. Most of us don't know enough about Egyptian society to understand the context completely. But we may be surprised to find the peasant's ruminations interesting.

The first reaction may be of disappointment—hey, where'd the narrative go? This is just speeches now?

But once you accept this, you may see how profound this material must have been for the ancient Egyptians and for those who came after.

Two collections of ancient Egyptian works that include "The Eloquent Peasant" are The Tale of Sinuhe and Other Egyptian Poems, translated by R.B. Parkinson, and The Literature of Ancient Egypt, edited by William Kelly Simpson but with this story translated by Vincent A. Tobin. Parkinson's translation is the seminal translation that scholars seem to depend upon. Tobin's builds upon Parkinson's and is the easiest to read and understand in my experience.

At this writing, there are also several versions available for reading online but I find them too crude to get across the meaning of the peasant's monologues in any way that would impress a modern reader. Some of them also compress the story, leaving out most of the poetic speeches which are the heart of "The Eloquent Peasant".

— Eric

Critique • Quotes